V.Vale is a SF punk publisher who never quit. He’s been doing counterculture publishing since 1977, when he founded the punk tabloid, Search & Destroy. I recently met with Vale and his wife Marian at their pad in North Beach to explore more of the story …

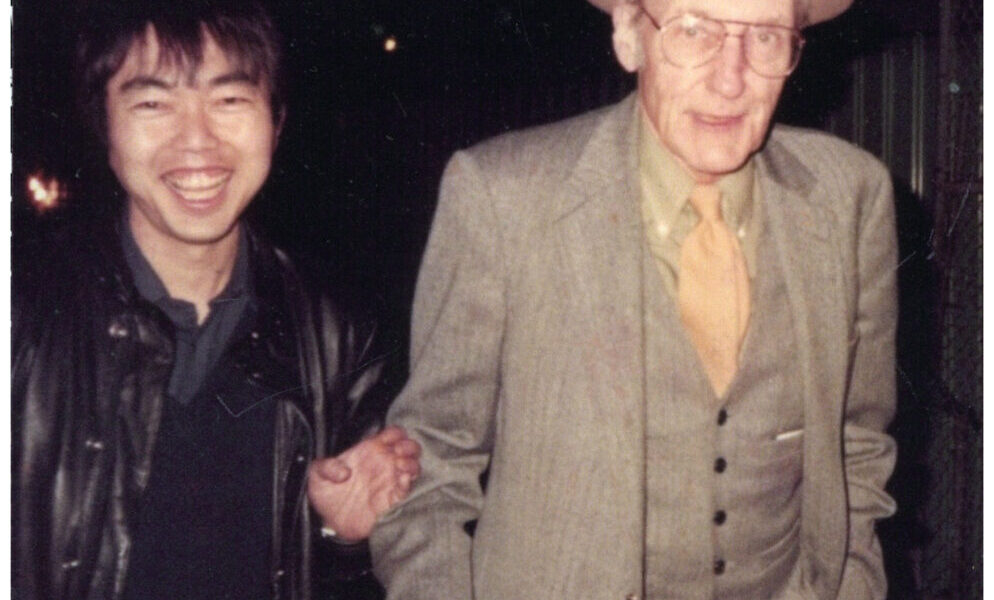

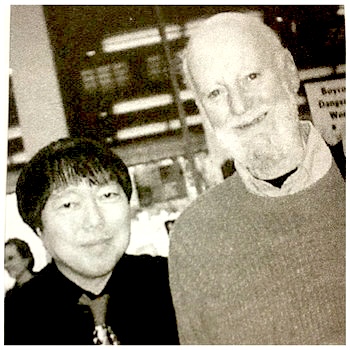

VV: I’m in the front of this photo because I was the only person in the band who knew Jim Marshall. I had joined this band Blue Cheer around August 1966. I was backstage at the Avalon Ballroom with a really cute girl, by accident I might add, and Jim Marshall invited us over and showed us his photos. He had pictures of pre-psychedelic stars like Joan Baez and other folk music types. Hippie music grew out of the folk music movement.

HSV: What brought you to San Francisco?

VV: I had applied to UC Berkeley, I knew my uncle lived in SF, I guessed he’d help me out and he sure as hell did! I stayed at his place for free. Lawrence Ferlinghetti and my uncle were in WWII. There was this great thing called the GI Bill. If you fought in WWII, they would pay for you to go to college anywhere in the world. Ferlinghetti and my uncle wanted to become painters and went to the Sorbonne. That’s how they met. Then my uncle followed Ferlinghetti when he moved to SF and started City Lights.

Way back when, counterculture had to do with reading forbidden books like Tropic of Cancer and Naked Lunch. They were not taught at UC Berkeley but you knew this was what the hip people were reading. An alternative vision on how to live. Instead of settling down and all that. You definitely didn’t get a straight job — although I did. Starting in ’67, I worked at City Lights. I was a lowly book clerk. I started their mail-order business because that would give me power to order books. That was the way to meet anyone who mattered as a writer. I glommed on William Burroughs. It has to do with some level of rebellion in your soul. Punk rock was the last big counterculture.

HSV: Search & Destroy started with money from Ferlinghetti and Ginsberg?

VV: Ginsberg gave me a hundred. I showed it to Ferlinghetti and he immediately wrote me a matching hundred.

Hop on the Haight Street Voice bus and support local journalism!

If you’re kind of born a rebel child, you’re always gonna rebel against the status quo you were raised in. The Punk Movement was a dialectical reaction to the Hippie Movement. You write about what pisses you off about the world. But more than that, you use black humor.

HSV: Wavy Gravy in the middle of a protest putting on a clown nose.

VV: Right. Everything that pisses you off about the world, don’t get mad at it, make fun of it. I like punk because punk made everybody — people put on shows in their living rooms for free.

HSV: Is it possible to keep that connection going?

VV: Provide a social matrix, a center gathering point where people can meet and do whatever!

FULL TRANSCRIPT

HSV: It is December 11, 2024. I’m here with Marion and V.Vale and we are talking ultimately about — the cover story is the Counterculture Museum coming into the Haight Ashbury. But the whole arc of the counterculture, my friend — we always say the Beats, but my friend goes even earlier saying it was the Bohemians in France …

VV: Oh yeah.

HSV: And then arcing into now and where are we going from here is what I’m kind of trying to pick up the pieces about. And hearing what you landed and all of that. So I will start with this because I know you lived in the Haight Ashbury. I would love it if you told me about this photo (Vale on corner of Haight & Ashbury) What year is it?

VV: This is in the spring, I would guess around May 1967, April or May is my guess. And the reason I’m in the front of this photo is cuz I’m the only person … before then I had joined this band called Blue Cheer around August 1966 I guess. August or September of ’66 I saw an ad at the Psychedelic Shop. They had ads in the front and they put up little ad. The ad said, “Blues band starting like Paul Butterfield. Drummer wanted.” But I wasn’t a drummer, I played keyboards so I said, “Well I play keyboards and I know the Paul Butterfield Blues Band record.” And they said, “Oh yeah, you can join.”

But see, I was the only person in the band that knew the photographer, Jim Marshall. And the reason I knew the photographer was because I was backstage at the Avalon Ballroom and I was with a really cute girl — by accident I might add — and somehow he invited, he really invited the girl but I was with her, quote “with”. Never went to bed with her or anything. And so he invited us over and he showed us all his pictures. And he had pictures of himself with various pre-psychedelic stars like Joan Baez, Joan Baez at her house, and Mimi Farina and — anyway just a few other more or less folk music types. Cuz the hippie music grew out of the folk music movement.

And you’re right about the Beatniks here being preceded by the Anglo-French, whatever you called them in France, right after World War II …

HSV: Gertrude Stein?

VV: That’s way earlier. That’s the 20s. That’s when people like F. Scott Fitzgerald and Hemingway were so hip they moved to Paris then, and got to know Gertrude Stein, and she documented part of that, and they wrote about it.

But anyway, the point is that Lawrence Ferlinghetti was in World War II and my Uncle Kayan, a Japanese guy, was in WWII and they both, there was this great thing called the GI Bill that if you fought in WWII they would pay for you to go to college anywhere in the world, and they would pay your expenses, the college tuition and money to live on. The GI Bill they called it.

And both Ferlinghetti and my uncle decided “Oh we wanna become painters”. They both went to the Sorbonne and took a painting class. So that’s how they met. They’re both ex-pats from America. So my uncle kind of became a good friend of Ferlinghetti — as if he had any friends — and my uncle followed Ferlinghetti when he moved to San Francisco and then started City Lights Books.

HSV: Was Ferlinghetti from here? I should know, I can look it up.

VV: No, no. He was from the East Coast.

HSV: What is it about San Francisco that drew all these people here? I mean I’m from here and I said fuck this and moved to New York. I kinda did the opposite. Only for 7 years. I came back. But I had to get away from SF.

VV: That’s a really good question. Why did Ferlinghetti and then my uncle, who followed Ferlinghetti here — why here?

HSV: I mean, it is the Wild West.

Hop on the Haight Street Voice bus and support local journalism!

VV: Maybe it was that!

HSV: My grandma came here around 1880 in a covered wagon from El Paso, Texas, looking for gold and all that. It was the final frontier, the Wild West.

VV: Maybe that was it. Cuz why didn’t Ferlinghetti just move to New York City, for example? That’s a really good question. I’m not sure anyone’s answered that!

HSV: I know that you were in — I think you said four foster homes by the age of 7 or 8.

VV: Yeah.

HSV: So what brought YOU to San Francisco?

VV: I went to UC Berkeley. But the reason I went there is because I got into Harvard and I went there and I was scared shitless of the campus, and I didn’t know a soul there. And the buildings looked so old! I wasn’t used to that at Harvard. But I had also applied to UC Berkeley and I knew my uncle lived in San Francisco and I guessed he’d help me out and he sure as hell did. I stayed there for free at his place.

I moved up here in the summer. I didn’t have any money. I had to work temp jobs, which I did to save up money to go to UC Berkeley. I got a scholarship there too but you don’t need it. It’s so cheap, tuition, if you’re a California native. I took an English literature major cuz that was the easiest. I said, “Ah to get paid for reading fiction.” (Laughter)

But anyway …

HSV: What year is this? What years were you at Berkeley?

VV: This is the ‘60s. ’64, ’65. I actually didn’t go to Berkeley until my junior year. I went to a small (inaudible) college my first two years. I lived in the college dorm. I moved away from home to be part of the college and my roommate and I were both kind of rebels. We said, “Fuck this small town! Let’s go to Harvard!” We both got in, but he stayed there, and he still lives there. He’s still alive.

The point is, at Berkeley I moved there really partly it was because of my uncle in Potrero Hill and he owned a house. He was always a real estate wheeler dealer. I know that he sold Ferlinghetti a lot in Bolinas for 3000 dollars, and I guess Ferlinghetti might be buried in Bolinas.

HSV: Wow.

VV: Anyway, the point is … what’s the point?

HSV: Well the point is, the reason I’m here, the Haight Street Voice, “hyper local with a global perspective” so the intention of the magazine is tuning in to your community. But to me, this Counterculture Museum opening on the corner of Haight and Ashbury in the same building I used to live in is such a blessing because it’s a place where everybody can land now and there will be books and you can read or you can watch hopefully a film or something.

VV: Right!

HSV: It doesn’t have to be — it’s not gonna be Jerry Garcia’s guitar or something like that, it’s gonna be fodder. I guess what I want to have this edition — cuz they’re on the cover — is: What does counterculture mean to you? Let me ask you that: What is counterculture? What was it then, what is it now, and where is it going?

VV: Well way back when it had to do with reading kind of forbidden books like Tropic of Cancer was notorious and Naked Lunch too. But Tropic of Cancer was even way earlier than Naked Lunch. And also reading Genet. I don’t know, there were these people that you knew somehow you had to read and they were not exactly taught at UC Berkeley and in literary history classes, but you knew this was what the hip people were reading. I don’t know how you found this out but you knew! Who else? There were a few other people too that are important … Simone de Beauvoir, the Second Sex. I mean there were books that were old …

HSV: I think you mentioned Camus?

VV: Oh definitely Camus! Oh god, The Stranger, oh definitely! To me, you had to read all the existentialists like Sartre, though he’s harder to read.

Marian: Siddhartha.

VV: Oh yeah! Siddhartha was another one you had to read.

HSV: Funny, I have that by my bed right now!

VV: You had to read Siddhartha, definitely. And then you had to read Herman Hesse.

HSV: Steppenwolf.

VV: Steppenwolf is the most famous, but then the harder one to read was there really thick book he wrote after that. Now I can’t think of the name, but …

[EDITOR’s NOTE: It’s either:

- Narcissus and Goldmund (1930)

- The Journey to the East (1932) OR

- The Glass Bead Game / Magister Ludi (1943)]

HSV: That’s okay.

VV: I have to look it up. But those were the people you had to read.

HSV: So it’s reaching for things that you don’t know that are kind of weird, or wanting to sort of get into this area of thinking.

VV: And they also have an alternative vision on how to live, like instead of getting a job and getting married and settling down and all that. It was different. You didn’t get married (laughs) or something. You definitely didn’t get a straight job I guess.

Although I did get a straight job. I only had one real job since graduating UC Berkeley, I worked at City Lights Bookstore. But I was a lowly book clerk, but I started their mail-order business because that would give me power to order books for City Lights. So that was nice, for various reasons. I remember it all happened because very early on when I worked there, I don’t think the store was very well organized.

HSV: What year did you start there? I just want to make sure.

VV: I think it was ’67.

HSV: And I’m assuming that’s how you met Burroughs and all of that?

VV: Oh! That was the way to meet anyone who mattered as a writer! I mean I remember meeting Simon Watson Taylor that you don’t know. He’s a famous translator of surrealists’ works. He showed up and a lot of people showed up that I didn’t have a relationship with But Burroughs I glommed on to because he was like Number One.

HSV: I leave my magazine over here sometimes and City Lights is so nice cuz they’ll let me leave it there. But I was in the Haight working at this little shop last year and this guy from France comes in and I handed him my magazine and he said, “Oh I already have it.” And I go, “Where did you get it?” And he said that he had picked it up the day before at City Lights Books! I just love the fact that it’s like this hub for people to come to …

VV: Right.

HSV: … Which I hope the counterculture Museum as well will be a place for people to land, community, and kind of connect. I call it “connecting the micro-dots” where you sort of connect with people who are on the same sort of wavelength hopefully and reading the weird books. (Laughter)

VV: Oh yeah, yeah, yeah! It has to do with some level of rebellion in your soul.

HSV: Being born with it?

VV: Probably. Where does counterculture come from and what IS it? Of course a lot of people came to the Haight Ashbury after mainstream articles appeared in LIFE and LOOK magazines and television, and then you had the Summer of Love in ’67. That wasn’t the Summer of Love! That was the “Summer of theft”! (Laughs). IThe real Summer of Love was the year before in ’66.

One of the earliest event things I came to — I depended on reading Ralph Gleason in the Chronicle. He gave early publicity to the beginning of the so-called “hippie movement”. He told me there was gonna be this thing at Longshoreman’s Hall that was — I guess the Merry Pranksters had something to do with putting it on? It was some — what was it called? It was some, very early …

Marian: What, the Acid Test?

VV: Yeah, the Acid Test maybe. [Trips Festival?] Yeah maybe that’s what it was called. And it was several nights at Longshoreman’s Hall down there. A round building with terrible acoustics.

On January 21, 1966, the Trips Festival began at Longshoreman’s Hall in San Francisco. The weekend was a landmark event in the evolution of psychedelic music that helped mark the beginning of the hippie counterculture movement. Photo by Gene Anthony.

Hop on the Haight Street Voice bus and support local journalism!

HSV: It’s still there, right? The one with all the round windows?

VV: Yeah, it’s probably still there, yeah. I haven’t been there in years.

HSV: So you were hanging around Kesey. Did you know Kesey?

VV: I didn’t know him but I’ve been in the same room with him.

HSV: And I know that you said in an interview that I was watching or reading that drugs were not your thing. Your two turnoffs were the drugs and the misogynist element of the Haight Ashbury was sort of a turn off for you.

VV: Yeah. I didn’t like either one.

HSV: So you came over cuz you loved the music, clearly, Blue Cheer was out of this world. I know that you were the keyboard player and then I guess they went to a 3-piece.

VV: Right.

HSV: But when you first came, that drug element wasn’t there like that.

VV: No, not so much.

HSV: People were smoking weed I would imagine.

VV: Yeah, weed, but very rarely acid. It was harder to get. And then I did try acid a few times, but I don’t like taking drugs. I don’t like smoking pot. Because they make me too quiet. (Laughter)

HSV: I always say I don’t need to obliterate my brain I’m trying to sort of pull it all in. Find out where I’m at. So where do you think the counterculture —

VV: Is headed?

HSV: Yeah. Where do we go from here?

VV: Well, of course punk rock was the last big counterculture. I think it’s still — I mean it’s had permutations like Nirvana, what do you call that — grunge. But that’s just another form of punk, just slowed down. Punk you don’t always just have to play fast. You can play slowed down.

HSV: Right.

VV: I mean you can do anything you want! Punk is DIY but I can do anything I want kind of.

HSV: Patti Smith, PJ Harvey, they slow it down.

VV: Well Patti Smith is super early. She’s maybe one of the earliest presagers of punk: ’74. I remember I read about her. Cuz I always — working at City Lights — I always read the Village Voice and the East Village Other, which has been forgotten, this weekly newspaper. And whatever else: magazines like Trouser Press … they were trying to chronicle bands. And ZigZag from England was trying to do that.

HSV: Melody Maker? Were they around then?

VV: The British weeklies all over the world that started punk. They gave the best coverage. Because they were weeklies, they had to have tons of interviews and these early bands that were later known as punk bands, they would give them a chance and give them a long interview. And find out what was going on counterculturally by these innovative bands that weren’t trying to be Grateful Dead imitators, but were trying to do something different. And so …

HSV: That’s a good segue. This is a question : With the publication of Search and Destroy, would it be accurate to call you the father of the underground press?

VV; Well, you can say I’m one of ‘em but I’m not the only one. I mean I think before I published, Sniffn Glue came out in England but it was really hard to get that in America. I think I actually had to do the unprecedented is send away to England for it, which is a pain, trying to get a money order that they can cash or something in British pounds (laughs). But the British weeklies definitely — the best one was between New Musical Express NME and Sounds. NME were they biggest but they were the most conservative. They would have the fewest long interviews with punk bands. And then the fourth one was called Disc & Record Mirror, which kind of looked like them but was way more superficial. They didn’t do much punk. Maybe a little.

But those four came regularly every week to City Lights Bookstore. I put myself in charge of doing magazine returns. In those days, I didn’t make much money at City Lights, minimum wage, but in those days you could return a lot of magazines by just cutting off the masthead at the top and retuning them. You had to mail them physically back to this place in Long Island, so City Lights would get credit. So I got to keep all the magazines with all the mastheads missing. It was legal.

HSV: And so did this inspire you to start Search & Destroy and Research?

VV: Well, what inspired me was I was huge Andy Warhol fan and he had put out Interview Magazine and as soon as he did I said to myself — I mean the earliest black and white issues were really crude and they were very badly edited.

HSV: And newspaper print! I was living in New York when it first came out.

VV: They were the same size as NME and Melody Maker.

HSV: They didn’t flip open they were just magazines, right?

VV: Yeah, maybe stapled. Anyway however, I used to own those very first Interviews. I don’t think I do anymore. But I remember thinking, “I could edit much better than this.” And they would include everything in the interview, unedited, like, (“He got up and went to the bathroom”) in parenthesis. I wouldn’t print stuff like that! And I’d also edit them down to the best thoughts, and the most concise.

HSV: The nuggets.

VV: Be as concise as possible and yet don’t kill their style.

HSV: Right.

VV: If you lose too much you kill their style, the style of the speaker. So I said, “I can do this for punk!” I knew punk was gonna happen and what it did, it took me months to physically produce the first Search & Destroy because I had never done anything quite like that before. Then I met some people who went to the Art Institute and they had some experience with graphics, photos, layout and all that. Well this guy that I really met named Violet Ray, that’s his pseudonym — he moved away a long time ago. He had a gallery on Grant and Green and I met him there. It was his proteges or friends, he brought ‘em all in to work on Search & Destroy. So I got handed a staff! They were all Art Institute kids. Some were very good artists and photographers.

HSV: And your first edition was a hundred dollars from Ferlinghetti and Ginsberg?

VV: Yeah ..

HSV: Burroughs?

VV: Ginsberg gave me a hundred. I took the check and showed it to Ferlinghetti who was a notorious tightwad — don’t put that in print — and he immediately gave me a check when he saw the check from Allen. I showed it to him and he immediately wrote me a matching hundred. Then I took those two checks and showed them to one of my only real friends who was an MD doctor who made way more money than the rest of us non-doctors.

HSV: Greased the wheels …

VV: And he said, “Ah! I’ll give you a check for $200!” And then someone else gave me a check for $25 and then I got some other money and then I put out the first issue and then kept going from that. It was hard to keep it going because it was hard to collect.

HSV: How often did it come out?

VV: I don’t know but I did 11 issues. The first issue came out July ’77 — later than I remember it. I thought it was June but I looked at my diary and it was actually July that it came out. Yikes!

From then until ’79 in those interim I did 11 issues. So it’s probably once every less than two months maybe.

HSV: Is ReSEARCH magazine a logical extension of underground publications of the ‘60s like Paul Krassner’s Realist and Allan Cohen’s underground newspaper, The Oracle?

VV: Well I mean in a way it is, except it’s mine! I’m the one that’s the filtering mechanism. I decide what to print and what to get, or try to get.

Warhol showed me, “Oh you don’t need to be a writer. You can just interview people with a cassette and transcribe the tapes.” And I was like, “Wow! That’s a lot easier than writing!” That was so brilliant! And so that’s what I did, to this day. But I can do anything I want. I can do a whole book on Burroughs, let’s say. Or a whole book on noise musicians, like Industrial Culture Handbook. Or I can do a whole book on underground films and call it Incredibly Strange Films. I did two volumes of Incredibly Strange Music, all about music that no-one’s ever heard of that came out on vinyl in the ’50s and ‘60s but were overlooked because they weren’t — they didn’t fit in the genres that had music magazine coverage like jazz. They have jazz magazines, rock and roll they have rock and roll magazines. But for these weird records — classical had classical music magazines — but for these weird, between the cracks things that came out like, I don’t know — there’s just a lot of weird records that came out that are unclassifiable.

HSV: Is it possible to find weird anything anymore?

VV: Garage sales. People die. Garage sales and flea markets. People die, they take their stuff to the flea market and sell it. Same for garage sales. In fact that’s where I got most of my record collection — at least 10,000 records to do those Incredibly Strange Music projects. The prices were great! They’re all from garage sales, thrift stores, or flea markets. Those three. And then some of them were from used record stores that didn’t know what they had and they’d sell ‘em for a dollar or something.

HSV: So are there treasures still out there? Again, I’m kind of bringing it back to where is it all going …

VV: I would like to think so. I think there’s treasures still out there because people keep dying. (Laughter)

HSV: And they’re gonna keep dying!

VV: (laughing) Yeah, that’s not gonna end soon.

HSV: I think you said in one of your interviews that the young people are hungry for the weird. There’s always gonna be a hunger for the weird.

VV: And the new. Yeah, something that I’m familiar with, like, “Wow, this looks interesting!” And often the artwork on the cover is as valuable as the musical contents. You just take a chance cuz, “Wow, that’s a weird cover!” And that’s not gonna stop, I think. There are three used record stores in two blocks.

HSV: That’s a good little jump: What do you think is the connection between North Beach and the Haight? There is definitely some sort of — whether it’s a vibe or a geographic energetic or something. There is a connection, I mean Allen Ginsberg hanging with the hippies. What is the lineage?

VV: Oh yeah! North Beach of course made sense I think greatly thanks to City Lights Bookstore but also thanks to the proliferation of small for-rent spaces where you could start a small bar like up the street. There was a place called The Place. I think my biological dad who was a Beatnik hung out there. I don’t know where it is. It should have a plaque on it whatever building it was.

Remember the big-eyed Keane paintings? That had some tie-in to the Beat Movement. Those Keane big-eyed children …

HSV: Oh yeah! Totally. Absolutely!

VV: There’s a movie on it that’s actually very good called “Big Eyes” I think. I only saw that recently.

HSV: I thought you were talking about Carol Doda’s blinking tits.

Hop on the Haight Street Voice bus and support local journalism!

VV: No! This is before then!

HSV: Okay.

VV: This is ’61, ’62 era. Carol Doda, I don’t know when … she was ’68? [Correction: Wikipedia = ’64] It was after the hippie movement I think? Well actually, it wasn’t that far after cuz I remember I knew some girls who were in a topless band that played there, an all-girl topless band.

HSV: (laughing) I digress! Going back to big-eyes artist, Keane.

VV: Yeah, and he had a gallery right there. Well if you saw the movie, he kind of ripped off his own wife, Margaret, who was the real painter of the big eyes. The movie is interesting. It’s worth seeing.

I mean, he was very good at promotion, Walter Keane was. But turns out he really wasn’t the genius painter! It was his wife Margaret Keane who didn’t get credit until this movie came out, “Big Eyes” recently, maybe 10 years ago or something.

HSV: But what do you think — again, going back to the bridge between, again bringing it [to the Haight and North Beach]?

VV: Oh yeah, North Beach! Because North Beach, I mean, look, we had the coffee gallery here. There weren’t that many places where if you just come to town and you wanna see a play or music or simple or something — you could play there.

HSV: Grant and Green [streets]?

VV: Yeah, Grant at Green! Janis Joplin first played there, sang there. But the Haight Ashbury was a totally different thing. It was also a genuine counterculture community that formed, but separate from North Beach. But I would say there were ties to it — philosophical ties if not geographical. They’re two geographical centers. But we have City Lights here. City Lights was actually a punk center. When people came to town and wanted to meet, there weren’t many places in North Beach you could hang out, except for Caffe Trieste and City Lights. Though I suppose a few people went to bars but they’d have to be over 21 to get in, to go to Vesuvio or Specs across the street.

HSV: Right.

VV: But all of those were meeting places, especially the Trieste because that could be all ages.

HSV: To this day.

VV: To this day.

HSV: Speaking of that, we need that in the Haight again. There’s again, the Counterculture Museum, but a place where people hang out and share ideas.

VV: Yeah, like the Psychedelic Shop.

HSV: The Thelin brothers, right?

VV: Yeah! Where they played weird music too all day. Music from India or wherever it was from.

HSV: Alright [looking at notes].

As a founding member of Blue Cheer were you part of the hippie movement in the Haight Ashbury? And if so, what led you to gravitate to the punk scene in North Beach?

VV: Oh, that’s easy …

Well, the hippie movement had flaws from the beginning. One, definitely, I think it was — I was very much against so much casual sex. You’d meet someone and an hour later you’d have sex? Wait a minute! Don’t you think you should get to know the person a little better?

And I thought women were being exploited. And also, it was an all-white movement. There were hardly any people of — even my race there. Or blacks for that matter. And I was also against this emphasis drugs. But of course, I mean practically everyone if you went to visit their house in the Haight, the first thing they’d do is offer joint. And I’m like, “Wait a minute! I don’t wanna smoke pot.” So those two things were wrong from the start, to me, with the hippie movement.

And the punk movement that started as a reaction to that was totally antithetical. It’s obvious.

HSV: Not a lot of blacks in the punk movement.

VV: No! These are all white movements.

HSV: Minus the Black Panthers of course but that wasn’t music.

VV: That’s totally different! I remember when the Black Panthers would sell their magazines on the street, at bus stops and stuff they’d be hanging. You’d give ‘em a quarter and buy their magazine.

HSV: Sorry to interject. But that was a political movement, clearly.

VV: Yeah, that’s definitely political. Political, but it started here in the Bay Area, and that’s a different. That had people living in Oakland and Hunter’s Point, which is where — and the Fillmore, which is where the black people lived.

HSV: And some in the Haight too, even.

VV: Not too many.

HSV: But wouldn’t you say the Beat Movement and the Hippie Movement and the Punk Rock Movement — those were all political?

VV: But different. I mean, sure, there were protests. In 1965 at UC Berkeley we were protesting the Vietnam War, like, “What?!” And then there started to be protests in San Francisco too I remember. And then I remember some nights the people, the monitors leading the protest parades would be people I recognized from political groups at Berkeley.

I mean … there’s always … Okay! If you’re kind of born a rebel child, you’re always gonna rebel against the status quo you were raised in pretty much. But what happens if you’re parents are hippies? (Laughs)

HSV: That’s kind of why I said screw the hippie shit. I’m moving to New York.

VV: Yeah! (laughs)

HSV: I wanted to get stuff done, you know? instead of, “Whatever, man …”

VV: Right.

And again, the Punk Movement was a dialectical reaction to the Hippie Movement. Hippies wore bright psychedelic colors. Punks wore mostly all black, or just certain thrift store clothes. The Ramones popularized the black leather jacket but most punks could not afford them. I mean they were way too expensive to buy. But I tended to start wearing all black around ’76. I still do. But it’s just — that way everything matches and it’s fine! (Laughter) And if you travel, you can wash your clothes less.

HSV: [looking at notes] Okay, that’s the end of that batch. Alright. I won’t keep you too much longer. I don’t even know what time it is.

Okay I already asked, “Is it impossible to have an underground today?” And then I know in one of your interviews you said you should only have about 10 friends and create your own underground. I love that answer.

VV: Yeah! Yeah. And there’s still young kids today doing punk bands. And what is it? What kind of lyrics would you write? You’d write about what pisses you off about the world in general. But more than that, you’d try to use black humor and make fun of it. That’s always better.

HSV: Isn’t that kind of what the Pranksters did?

VV: Yeah, the Merry Pranksters!

HSV: Wavy Gravy in the middle of a protest would put on a clown nose so he wouldn’t get arrested.

VV: Right, yeah!

HSV: Humor is a huge thing. In fact I wrote that down.

VV: Black humor is a big part of punk rock I think. Everything that pisses you off about the world, don’t just get mad at it, make fun of it! Black humor.

And punk bands — still I like the idea of a punk band but these kids now can do a band with one person cuz of all this fancy electronics. You can have one person get up and it sounds like they have a drummer playing, a bass player, and all this stuff. And it’s all done on a computer with just a little setup.

HSV: That’s kind of on my mind too: How do we … there was much more community-oriented … you had to go rehearse with your band. You couldn’t just sit in a room and do it yourself. I mean that’s been going on for a while, but I just feel like covid — the whole thing where we are in 2024 going into 2025, it’s really hard to get everybody to come together.

I mean they had the punk rock photo exhibit at the Haight Street Art Center — shoutout to them — bringing all these old-school people together in one room, which was wonderful!

VV: It was nice!

HSV: So how do we … is it possible to keep that community stuff going? That connection?

VV: Well it’s usually one person in a town or city is a mover or a shaker and provides a social matrix center gathering point where people can meet and do whatever: rehearse a band, just work on a zine together, whatever forms of creative — start a silkscreen studio where you can make your own shirts with your own messages on them. We’re in the era of message clothing. We have been for awhile. People have some outlandish thing on their t-shirt and they get a lot of satisfaction wearing them.

Another good thing that the hippies did that’s been forgotten, I think they started the rage for vegetarianism, veganism, and growing your own produce, and not just taking it for granted. Starting your own garden or organic farm and all that, which I’m in favor of.

HSV: Yeah, absolutely! I interviewed Peter Coyote and he talked about moving to the country and having a commune and growing their own food. But that, you know, that fades away too. He said once people start having kids, it’s too hard to sustain.

VV: Too hard.

HSV: It’s not sustainable. People — again, about keeping everybody together and how do we do that, people separating cuz they all have to go off and do their own thing.

I don’t even really know what my question is but … I don’t feel isolated cuz I’ve got my magazine, so I get to go out and talk to people a lot and bring that all into one space that hopefully keeps people sort of connected, which I’m hopeful for.

VV: Yeah! You’re doing your bit. People like you we need!

HSV: (laughter) I didn’t mean to put myself into … whatever! My question to you on that note is: What would you like to say to the Haight Ashbury community and all communities today?

VV: Well I think like I said, get 5 or 10 friends together and just meet and try to do something creative like put out a zine, put out music, make a video — I mean you can do everything now with these iPhones! You can put stuff free on YouTube, I mean it’s kind of an amazing time. I never, before you had Xerox machines, like how would you do a zine?! There were no Xerox machines during the hippie movement and there weren’t any zines as a result. But with punk they started doing zines right from the beginning because the Xerox technology had become available, like I said before, the first chain of Xerox machines for the people was Postal Instant Press – PIP. You could go in and you could copy anything for a nickel or a dime. You could make a little zine and copy it and sell it for a dollar or something.

In other words, that’s why I came up with the aphorism, “First technology, then culture.” Because now — I mean it used to be you couldn’t make films or then the earliest video equipment was really expensive, those cameras. You’d have to get them from an art store or something, borrow them, and make your first early punk video, like Target Video.

But now, anyone can. You can do anything. You can publish, record, make a movie — it’s amazing what you can do with an iPhone.

HSV: It is pretty profound. On the other end of the spectrum …

VV: … and share it!

HSV: And share it. I’m happy to know that people still want print.

VV: Oh yeah. Tangible.

HSV: I would’ve thought in my head print would go away but it didn’t thank god.

VV: No. I like print. And one reason I like it is because once it’s there, you can’t sensor it. You can change anything anytime if it’s online. There can be little subtle changes and maybe not always for the best. If you do a so-called online zine …

Also, it’s an economic thing. If you make a little zine, people give you a little money.

HSV: Right. This is free (holding up HSV). I make money from the ads and subscriptions.

VV: Oh! Well that’s good.

HSV: I like just giving it to people. They’re like, “Wait, what?” That’s a whole different program though.

VV: Yeah! I never did that! (Laughter) I always charged.

HSV: I always have this fantasy of bringing people together and having a round table.

VV: Oh yeah.

HSV: Like 10 people or so. You don’t have to make anything or whatever, just people sitting around a table and maybe nothing happens, but just the think-tank kind of thing.

VV: That’s a good idea.

HSV: I really would love that. People like Mark McCloud, who you know.

VV: Oh yeah! What a character! I just saw him!

HSV: Oh good, and I love Cynthia, she runs the Psychedelic SF Gallery in the Haight.

VV: She’s great. I just saw Mark at Gray Area, I had a book table at Gray Area for the Recombinant Festival last week and I saw Mark McCloud there. I was very happy to see him.

HSV: I think that may have been what you want to say to the Haight community and all communities … the finale.

VV: Yeah, find a few friends and do stuff with them. In fact, only make friends that you do stuff with!

HSV: “Wanna do stuff?!” (Laughter) [reviewing notes …] Are things more complicated now than they were when you began you’re whole thing?

VV: Oh yeah! But the world’s so much more complicated you actually have to spend a lot of time saying no to a lot of the media. You just don’t have time anymore! There’s too much. There’s too many things to worry about now.

HSV: Paying rent.

VV: Yeah, well paying rent has always been number one. And it hasn’t gotten better. I mean it’s such a radical idea to introduce to America: You know, everybody who needs it should get free rent. (Laughs) But what about the real estate lobbies and all of that. You can argue that all the people who built all the houses they’re long dead and why shouldn’t they turn into free housing? But that’s too radical a thought.

HSV: The light that lit the ‘60s, how do we keep it burning, how do we keep it going, how do we keep it moving forward? Again, probably getting together and talking with your people, yeah?

VV: And again, I like punk because punk made everybody — I mean I know people who put on shows in their living rooms for free, or their basements, or occasionally a block on the street illegally and have a little concert somewhere down south of here. And obviously you make your own clothes or your own style from thrift stores. There are clothes on the street now all the time. And again, there are so many ways to make music now you don’t even have to buy a guitar and amp. Jesus! (Laughter)

HSV: Okay, one last thing I just realized: is that … ?

VV: That clock is wrong.

HSV: Oh, it’s 3:12, I’m late. Sorry Jerry [Cimino, down the hill at the Beat Musuem on Broadway]! But here’s one last thing, speaking of which: How do you feel about the Counterculture Museum? What are your hopes and dreams for it?

VV: Oh! Well it deserves to have a museum! Which is also a library, an archive.

HSV: Some asshole on Facebook when I posted that the CCM was coming to the Haight he said, “Oh once you make it into a museum, you know it’s dead.”

VV: Oh, that’s a cliche!

HSV: I replied: “What, does that mean art is dead?”

VV: (laughs) Yeah, right?! Everyone’s still making art. I love the idea of making art and giving it away.

HSV: So you think the Haight Ashbury deserves a museum?

VV: Oh hell yes!

HSV: She’s earned the right …

VV: Oh yes! A museum / archive / library …

HSV: Hanging spot too.

VV: Hangout spot. Even occasional free snacks!

HSV: Maybe some musical thing once in awhile.

VV: Yeah or a small coffee shop or something.

HSV: Maybe one of Marian’s movies or something! A screening. Well okay! Thank you both so much, yay!

VV: Yeah, thank you!

HSV: (to Marian) Anything you want to say to the Haight community?

M: Don’t let it get you down.

HSV: The “it” being?

M: The big “IT.” Keep going. Keep at it.

VV: And Marian likes to encourage everybody to make amateur independent films.

M: Yeah, right.

HSV: Especially now that you can do it outta your frickin’ phone. Alright people, peace out! I gotta call Jerry and tell him I’m late.

VV: Tell him it’s all my fault!

Hop on the Haight Street Voice bus and support local journalism!