Premiere edition of Haight Street Voice, February 2017

Long-time music journalist (and my teacher-mentor-dear friend) Ben Fong-Torres, started his career in the ‘60s, interviewing throngs of soon-to-be famous musicians, and eventually became a staff writer for Rolling Stone magazine and a well-known radio personality here in the Bay Area. We spoke with Ben via phone recently and gleaned a few words of wisdom from him about journalism — then & now.

Haight Street Voice: Okay, we’re merged. Always nerve-wracking, these tape recorder devices, aren’t they? Did you ever have one of those interviews where none of it was recorded?

Ben Fong-Torres: Yes — it’s a horror story! You have to call back and apologize and finagle them to repeat the same crap over again.

HSV: What’s your thought on journalism and the Haight back in the day, and where journalism is today?

BFT: I would drop by the Haight just out of natural curiosity and enjoy the scene. If there was music going on, I might check that out at the park or just mostly hang out. But most of my hanging out and talking to people would be probably be on campus at SF State and socializing at the Fillmore, the Matrix, the Avalon — like that.

In terms of journalism, the primary newspapers of the day that kind of covered that scene were The Oracle, which was in the Haight on the street:

San Francisco Oracle, Volume 1 #7, March 21, 1967

and the Berkeley Barb, which was an underground paper, multi-political:

The Berkeley Barb, Volume 5 #24, December 15, 1967

but still pretty much had to cover what was happening in San Francisco as well as Berkeley, even though the two scenes were rather different. One was political and one was almost absolutely non-political and more about lifestyle.

And then you had, later on, Good Times:

Good Times, April 9, 1971

They were kind of mix of the two themes: Being in San Francisco, very quite political and activist and yet also attuned to the arts, and graphically more sophisticated than the Barb.

Those were the papers I was most interested in seeing. The Oracle in its own way was revolutionary, but not necessarily journalism. It was commentary, it was commenting on the scene, rallying people to the Human Be-In, profiles of community leaders, and sort of sometimes a bulletin board for the Diggers’ activities.

With the Barb, people would bring it over from Berkeley and sell them on the streets. I remember that in that documentary about the Haight-Ashbury called The Revolution there’s this young, blonde girl named “Today” who in one long scene has a large stack of Barbs and is trying to sell them to tourists coming through on one of those tour-guided busses that came to get a look at the hippies. That seemed to be the way Today was making her living, I’m sure she wasn’t alone, and that’s how the paper got some of its circulation. She’s actually still around: Today Malone.

HSV: Where did writing for Rolling Stone all start for you?

BFT: I had been the editor of the paper that covered the scene out at SF State. I was writing about some of the musical things going on on campus and witnessing things like the Blues Festival or the Folks Festival, which got hyphenated into rock, and also visits by such groups as the Great Society, which had Grace Slick as their front gal before she joined the Airplane. This was 1965 or 1966, somewhere around there. And the same thing with Janis Joplin, in one of her early rehearsals with Big Brother when she arrived from Texas. They chose to hang out at SF State because the Albin brothers were students there, or at least one of them was, and they took over a little art gallery on campus. They had a practice session and I happened to be walking by. So that’s how that started. I was conversant with that scene and a pretty wide-range of music.

I had a tremendous love of music as a kid, I listened to it on the radio all the time. So by the Rolling Stone came along in late 1967, I’d had another job or two on the radio and at the phone company magazine, but I was reading Rolling Stone from the very beginning.

All my roommates were media related in terms of work and interests, and one of them told me about a free concert in a nearby park to promote a movie about Haight-Ashbury by Dick Clark. So my little journalism antenna sprang up and I called Rolling Stone and said, “Do you know about this?” They didn’t, so they said, “Sure, we’d like to have a few paragraphs about it.” So I submitted my first little item for the paper, and that was it. No byline, no nothing, very little pay — five bucks maybe. But it didn’t matter. It got me into what was emerging to be all of our favorite publication around the music scene — especially around San Francisco.

Then I pitched other items and they began to assign me stories. And then about a year later, Jann [Wenner] invited me to have lunch and talk about my jumping on board. That was the Spring of ’69. I was there by May as an editor and writer.

Rolling Stone was in the South of Market before it was SOMA, in terms of a trendy neighborhood. It was just an industrial warehouse area of town on Brannan and 7th, not too far from the Hall of Justice. That’s where Rolling Stone set up shop ’67 to ’70. Then we moved to the MJB building on 3rd between Townsend and Brannan. Rolling Stone was never in the Haight-Ashbury.

HSV: Coming from someone like you who’s been there from the very beginning in SF and rock journalism, what would like to see in Haight Street Voice? What would make you happy to see in a magazine like that?

BFT: Well, I don’t live in the Haight, but if I think that a publication should check and see what the state of the community is in terms of the people living there, what binds them together and what interests they might have in common, what particular fears they might have — whether it’s local issues or global — and see what semblance there is of what the spirit used to be 50 years ago, and see if there are sparks of that around.

It seems that whenever I’ve reported on the Haight, there’s talk about gentrification, there’s talk about yuppie-ization, there’s talk about the stores coming in that are changing the face of the neighborhood. And of course, whenever that happens, there are the pros and the cons, those who want to preserve the historic nature of the neighborhood and not have new retailers coming in and putting in Z-Galleries. Then there are the “fors-it” who say, “Come on, grow up. We do want to have a furnishings store or a decent bookshop or a Whole Foods Market” or whatever it is that goes in there. There’s always going to be the two sides battling it out, and that’s not gonna change. And so a publication can serve the function of trying to raise the various sides of an issue — let them be aired.

A publication needs to be out there on the streets and online, and encouraging feedback and comments, and then, who knows, maybe have occasional meetings at the park or the Red Vic. You could have a representative from City Hall, depending on what the issue is, a musician — whatever.

HSV: We want to give voice to the people and spirit of this neighborhood today, as well as what it represented in the ‘60s.

BFT: People around the world still have a romantic memory of the Haight, whether they were ever here or not. It was such a phenomenon that it continues to inform people about a certain way of life attempted here. And for those who couldn’t do it 50 years ago, or a new generation of kids who wished they could’ve had their parents’ moment of experimentation — I think they would like to read more about what did happen.

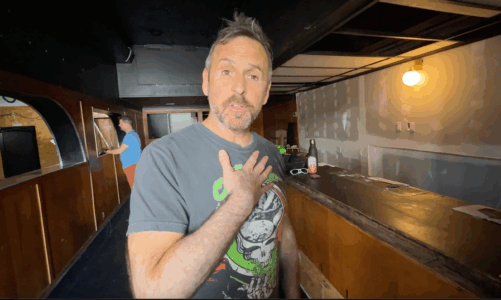

Ben Fong-Torres (R) and Linda Kelly (L) at the Stanley Mouse (far right, background) art exhibit, 1506 Haight Street, Summer 2023. NOTE: I’m holding the Summer 2023 “Dog Days of Summer” edition of HSV. Ben’s dog, Marley, is one of the pooches featured on the cover. Ben wrote and recorded a song, “On the Cover of the Haight Street Voice” — a spinoff of “On the Cover of the Rolling Stone”. Love you, Ben!