by Ben Fong-Torres

[Photo of Jerry Garcia by Herbie Greene, 1966]

“It seems like hundreds of years and it also seems like not too much time at all,” Jerry Garcia was saying. “I don’t know. Time. Some things haven’t changed at all, really—and the world has changed.”

He was talking, in 1976, about the Summer of Love, ten years after. Only it wasn’t ten years after. The big, ecstatic, scary, media-driven Summer in San Francisco was in 1967. But Rolling Stone magazine, where I worked, decided that the scene had begun in ’66, and to Hell with other media and their anniversary celebrations.

After all, it was just a matter of … time.

Hop on the Haight Street Voice bus and support local journalism!

No one knows just when the Summer of Love actually started. It took shape, certainly, in San Francisco and Berkeley — but also in Palo Alto and in Cambridge, where Ken Kesey and Timothy Leary were experimenting with, and handing out doses, of the hallucinogenic LSD. That was back in ’64 and ’65, when the Warlocks, who played at Kesey’s parties, hadn’t yet renamed themselves the Grateful Dead; when folkies, led by the Beatles, the Stones and Dylan His Own Self, embraced rock music, and gathered at trippy dance concerts.

But if you were more inclined towards politics than parties, the societal changes began earlier in the decade, when college students created enclaves of budding activists, protesting against a war in Southeast Asia and for civil rights in the South.

In the Bay Area, Berkeley was the hotbed of political activity, culminating in the Free Speech Movement, sparked in 1964 and making a joke of U.C. President Clark Kerr’s prediction, in 1959, that the students of “this generation … aren’t going to press many grievances. There aren’t going to be any riots.”

At San Francisco State, the administration responded to calls for free speech by putting up a redwood stage on the campus quad, available to pretty much anyone who had — or thought they had something to say.

And that’s where I was at. For me, the year was 1965. I’d spent my underclass years hitting the books, so that in the Fall of ’64, I could join the campus paper, the Daily Gater. It was pretty good timing. I was just in time for the Sixties.

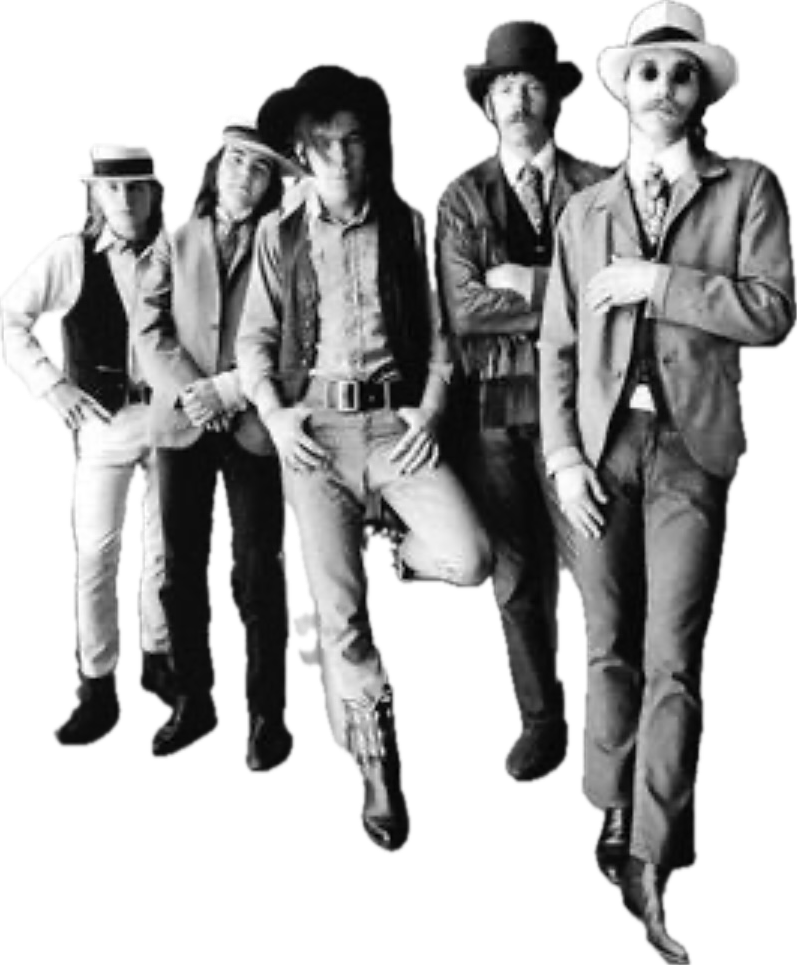

Against the drab backdrop of S.F. State’s cookie-cutter buildings, political activists stood out, making for good stories. By 1965, we couldn’t help noticing characters like George Hunter, a designer who dug rock music. He had Beatle hair and he’d show up almost every day wearing some kind of western outfit or a tapered Italian suit with pointy Beatle boots, and he’d hit the Tubs, a collection of barracks turned into student government and snack huts. He’d startle people by cranking up the jukebox and dancing by himself. Later, in the cafeteria, he’d join a table of hipsters and rap about politics, anthropology, dreams and drugs. His dreams included a rock band, and, although he didn’t play music, he put together the Charlatans. Hunter, his peers say, was the first dropout. Only he wasn’t a dropout. He was never enrolled at S.F. State.

I did an article about Hunter’s crowd for the paper, and the headline referred to them as “the happy people.” Many of them lived in a friendly, low-rent neighborhood called the Haight-Ashbury, and at night, they could be found at dance concerts being put on by Bill Graham at the Fillmore and by the Family Dog at the Avalon Ballroom.

George Hunter of the Charlatans, far left

Hop on the Haight Street Voice bus and support local journalism!

The Charlatans were ahead of the ballroom scene. They’d spent part of the Summer of ’65 in Virginia City, Nevada, at an old bar called the Red Dog Saloon, serving as the house band. They were better known for dressing up in old-timey threads and cowboy gear and for carrying guns and marijuana than for their music. Still, they were acknowledged as the first psychedelic band, and when they returned to San Francisco, they were central to the new, hip rock scene.

It was a whirlwind, but it was, it had to be a two-headed scene. There was, after all, the real world. Across the Bay Bridge, in Berkeley, the main concern seemed to be politics, and, to activists there, much of what was going on in the Haight seemed trivial. In San Francisco, the acidheads and “flower children” were content, for the most part, to stay apolitical. As Garcia said to one interviewer, “We just seek an uncluttered life.”

— California Magazine, July/August 2007

Hop on the Haight Street Voice bus and support local journalism!