“Nobody I know — and I mean nobody — has covered more ground and made more friends and sung more songs than the fellow you’re about to meet right now. He’s got a song and a friend for every mile behind him. Say hello to my good buddy, Ramblin’ Jack Elliott.“

— Johnny Cash, The Johnny Cash Television Show, 1969

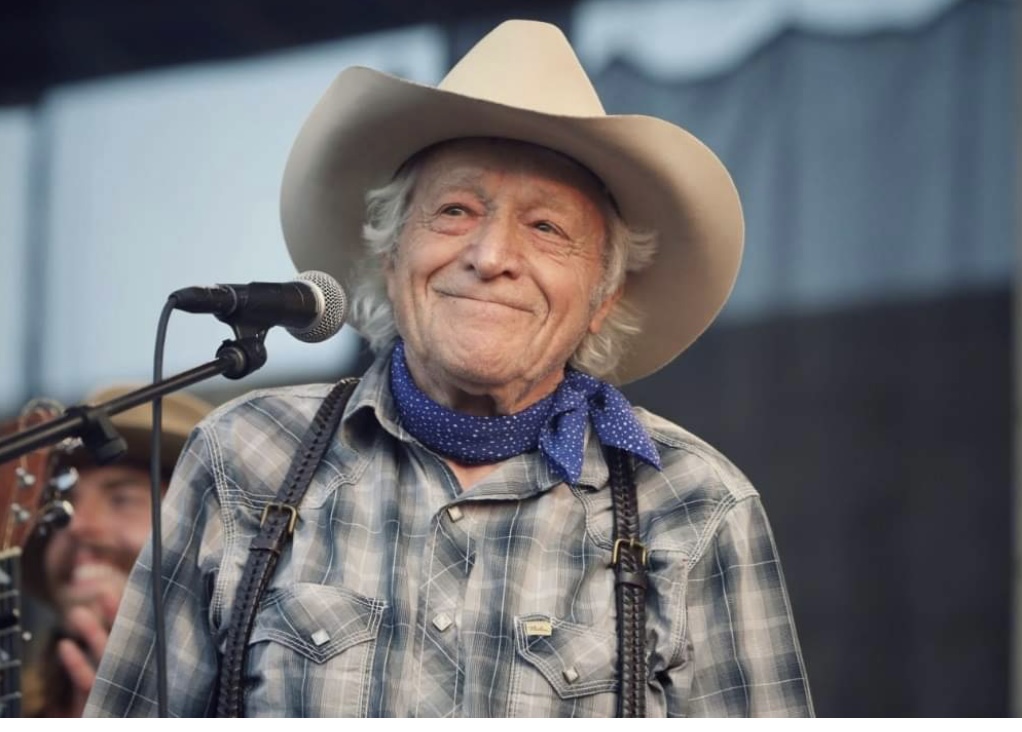

Storytelling through music is medicine. Sharing our experiences riding on the waves of a melody inspires hope in our soulds. And there’s quite possibly no better spinner of yarns than the ver-traveling troubadour, our good pal, Ramblin’ Jack Elliott, who’s still touring at 87 years old. In 1950, Jack became a dear friend and music comrade with folk music’s forefather, the great Woody Guthrie.

Since then, Ramblin Jack has traveled the world and been around all the heavyhitters: Leadbelly, Muddy Waters, Johnny Cash, Joni Mitchell, Kris Kristofferson, Rolling Stones, Grateful Dead and so many ore — and of course, Bob Dylan, who once was billed as “the Son of Ramblin’ Jack” back in the ’60s.

“Jack was King of the Folksingers.” — Bob Dylan, Chronicles: Volume One

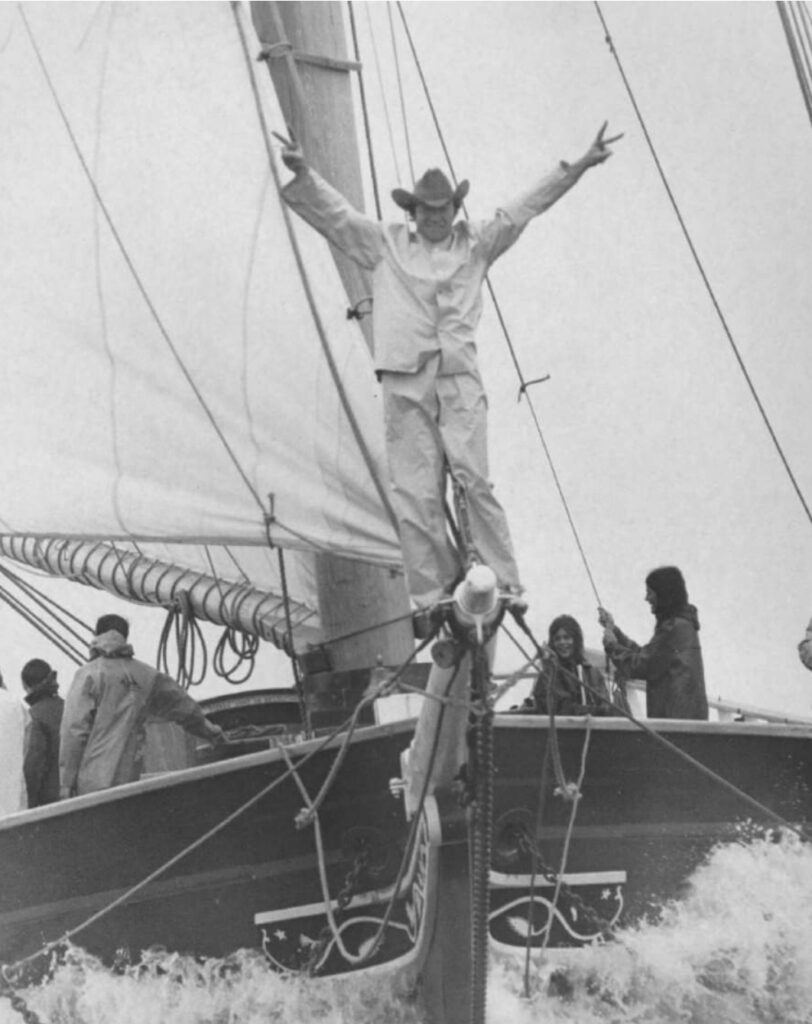

A great lover of horses, boats, guitars, and trucks, Jack digs driving the back roads of the North Bay and proudly calls himself “the slowest driver in Marin County.” With too much moving too fast these days, Jack’s calm presence is soothing, timeless. Listen to this living legend — both in song and in stories — and all your worries drop away as you realize the beauty in sharing experiences, simply remembering.

In this All-Music edition of Haight Street Voice, we tip a loving hat to Ramblin Jack, dust on his boots, sparkle in his eye, horses on his mind, boats beckoning. When the premiered issue of HSV came out in February 2017, the vibes of the Summer of Love were shining brightly in our hearts. Now, in these darker days of 2018, someone like Jack still being around helps lighten the load, his unbridled spirit an inspiration to just stop and listen. Look around. Ride a horse. Sail a boat. Strum a tune. Ramblin’ Jack comes straight at you, authentic to the core. He ran away from his Brooklyn home in 1947 at age 14 to join the rodeo, where a clown got him excited about playing the guitar:

“I don’t have a lot of secrets to my success, but when I get ready to go onstage and there’s this curtain and there’s this stagehand, and I’m waitin’ and then he turns to me and says, “You ready?” I go, “No” — and then I go out. Somewhere between him and the microphone, I get ready.”

In Texas, they have a thing down there called “South by Southwest”. Well, there is no such compass point! It’s “Southwest by South”. They got it bass-ackwards! But, you know, they’re 120 miles from any saltwater, so it don’t matter. South by Southwest? Ha! Nobody knows where anything is anymore.

Anyhoo, I was performing there and I went to see Kris Kristofferson. He was getting ready to do a show and we’re hanging out in his dressing room. You shouldn’t talk to an artist before they perform, but Kris, we have kind of a friendship goin’ and he was chattin’ away with me and I’m chattin’ away with him, and all of a sudden Kris says, “Ah, Jack, I’m gettin’ nervous, I’m gettin’ nervous.” I said, “Kris, do not get nervous!” I said, “The one thing I hate most is falling asleep onstage.” And he laughed! He got the joke. He laughed and he went out there and he did a great show because he relaxed and he forgot to be nervous.

[Here’s the full interview for your reading pleasure. He ain’t called “Ramblin’ Jack” for nothin’!]

HSV: What’s one of your favorite moments singing in front of a crowd over the years?

RJ: I’ve had a lot of those. I do remember the worst one: Neil Armstrong was setting his foot on the moon in 1969 at the same moment I set my foot at the microphone at the Newport Folk Festival, where 18,000 people paid a hundred dollars to see me, and it was raining. I remember I measured the speed Neil was comin’ down the ladder, and I’m walkin’ the same speed that he’s walkin’ so that I [slows speech] got-to-the-mi-cro-phone, pointed to the moon, and said, “He’s just stepping on the moon … now ….” like I could see it with my naked eye, which was bullshit. But it was true and everybody laughed. And then I started playing “San Francisco Bay Blues”.

HSV: What brought you to San Francisco and why did you stay here?

RJ: Originally I thought it was a really, really beautiful place, and I imagined how it might’ve been back in the days of the sailing ships coming in here to get grain, lumber. And I was walking around San Francisco with my guitar, an old Gretsch, ’75.

HSV: Do you remember what district were you in?

RJ: I was up in North Beach, I think, and Market Street, and then I wandered over to Harrison Street and I happened to see the SUP building — “Sailor’s Union of the Pacific” — and walked in. There were these fantastic, beautiful ship models. I was admiring these ship models and then I walked down the hill alongside the Bay Bridge approach, 1st and Harrison. I got down the Embarcadero and I got to a bar called The Anchor Bar. I walk into the Anchor Bar and ….

HSV: What year is this and how old were you?

RJ: 1951 — I was 19. So I walk in the Anchor Bar and there’s another ship model in there that’s a 5-masted schooner. They didn’t build a lot of 5-masted schooners. My brother, David, has a 5-masted schooner moored to a dock about a mile behind his house. There’s a little footpath and you can walk through the woods and go see the Cora Pressy — she’s a wooden schooner about a mile long.

HSV: Why would they go with 5?

RJ: With 5 masts, because it was a much longer ship, there’s a limit to how big the sails can be because the larger sails require that you hire more men and feed them and pay them. So they put more masts with smaller sails and had a crew of only 12 guys. They can furrow those sails by hand when the wind got too strong, cuz that’s the economics you’re limited by. You can’t have a sailing vessel with too much sail area unless you can afford to pay for a large crew to handle those sails.

HSV: So you walk into the Anchor Bar and you saw the ship model …

RJ: And it was a model of a schooner called the Inca, and I’m looking at the Inca model for about a half an hour, and then I ordered a beer and the bartender says, “Ya like that model?” I says, “Oh yeah!” He says, “That model was made by Eric Swanson, the same guy that made the bottles up at the SUP building. He lives around the corner in the Harbor Hotel, room 6, and he painted this picture behind me here of a 5-masted full-rig ship — the only 5-masted square-rigger ever built. The only 5-masted full rigger ever built. There’s been two 5-masted barcs and one 5-masted full-rig ship in the history of the world.

HSV: Why did you know all of this when you were 19 years old?

RJ: I love ships, and I wanted to know everything there is to know about ships. My next-door neighbor was a whaler from New Bedford. He was from New Bedford originally. He sailed in a whaling ship when he was about 13 years old out of New Bedford, Massachusetts. He and another boy took their clothes off, put ’em in a little bag, held the bag over their shoulder and did the sidestroke and swam out to — this is what he told me. I was 12 years old, he could’ve been lyin’ to me.

I was interested in ships already. I had my own copy of the Blue Jacket manual, 1940. This is the year 1943, I’m 12 years old.

HSV: Is that where your wanderlust came from?

RJ: One day, my dad told that the man who lives next door with the red face, he’s a sailor, he was a harbor pilot. He was bringing ships into New York harbor, guiding ’em in.

I’d already been reading the Blue Jackets manual and I was thinking of joining the Sea Scouts, and he gets out of a taxicab and he looks really disgruntled, he’s upset about something I can tell. So I waited until he paid the cab driver and he drove away and we’d never been formally introduced, I’m 12, and I said, “What seems to be the trouble Captain Hinkley?” He says, “Ah, I brought a navy ship in, a destroyer, the captain says, “I think we oughta go this way, I think we oughta go that way, I sent the captain to his room!”

The harbor pilot is legally in charge of the vessel and responsible for everything that happens to the vessel. Legally he’s responsible. If he gets stuck in the mud or hits another vessel and there’s damage and lawsuits, he’s responsible.

He’d been to Annapolis Naval Academy and after he graduated from there he went into the merchant marine and he was the chief officer of the largest ocean liner on the Atlantic. It was called “Leviathan”, which means “whale” in Latin. It was a 4-stacker, 4 smoke stacks.

I said, “What seems to be the trouble Captain Hinkley?” and he said [imitating grumpy voice], “Well, I sent the captain to his room.” And I said, “Well, I’ve been studying my Blue Jackets manual” and that hit him! He said, “Oh yeah? Why don’t you come up and see me tonight after supper and I’ll show you some things.” “Okay!”

So after dinner I went up there and knocked on the door. He’s got the living room, he had two beautiful daughters who were about two years older than me but I wasn’t interested back then. I was only interested in boats and a few other things. We sat there, he taught me how to box the compass: north, northeast, east, southeast, south, southwest, west, norwest, west. That’s 8 points. He taught me how to box a compass with 32 points.

HSV: So we do have to get back to the bar in San Francisco, but we are enjoying this story. How old were you when you picked up a guitar?

RJ: 15 — almost too old to learn. It was a rodeo clown that got me excited about playing the guitar. His name was Brahma Rogers, it was 1947. Some ranches in Montana, Wyoming, Colorado and Arizona in 1947 still used horse-drawn chuck wagons.

HSV: So back to SF and room #6 …

RJ: I went up the stairs, second floor, room #6, knocked on the door, and a little old Swedish guy with a very heavy Swedish accent with a big, full white mustache — I don’t think he was over 50, but it was like over a 100 from where I was looking at it. He was glad to have a visitor. He showed me all kinds of little tools that he invented to make ship models with. I told him I saw those models over at the SUP building and down around the corner at the Anchor Bar. His name was Eric Swanson. He was a sail maker and he’d been around the horn 12 times in square-riggers. Making sails, sewing them by hand, he said, “You like those models?” I said, “Oh yeah, I like those models!” He said, “You ever seen the big one?” I said, “What’s that?” And he said, “Oh, I’ve got a model in the marine museum.” I said, “Where’s that?” He said, “Oh at the other end of the waterfront.” And he told me how to get to the San Francisco Maritime Museum, which is at the foot of Polk Street. Near Aquatic Park.’

So I went over there, I walk in and the first thing I see is this model he built, took him 5 years. They paid him $5000 for the model, which is probably worth $500,000 today. It’s 10 and a half feet long, it’s a 5-masted full-rig ship, that means she’s rigged with square sails up and down every mast, 5-mast, 6 square sails, she was 407 feet on the water line, the bowsprit was about 60 or 70 feet long, the main mast was 220 feet high, and she carried 6000 tons of cargo, and she had water-tight bulkheads in her hull, which is very unusual for a sailing vessel, steel hull, steel mast, canvas sails, no auxiliary engine.

She was built around 1905, Germany, the ship. I don’t think she was ever in San Francisco. She was made to go to Chile for night trades, bird shit to make bombs. They had a whole fleet of the world’s largest sailing vessels from Hamburg Germany to Chile for bird shit to make explosives for World War I — before WW I, they were doing this in 1905 to get ready for WWI.

Cynthia Johnston: How do you make a bomb out of bird shit?

RJ: Bird shit contains nitrates/nitrogen mixed with some other chemicals can explode. And it’s for two purposes: either for bombs or fertilizer.

Did you ever hear about the Texas City Fire? During WWII, they were unloading some sacks of nitrates, fertilizer, in Texas City, it’s near Galveston, and somebody was smoking a cigarette and dropped an ash and it was like a trail of nitrate on the deck and cigarette ash dropped and caught fire like a fuse, it went to nearest sack from whence it had leaved and exploded and the ship blew up.

HSV: The ship and the shit …

RJ: Everything went up. Then the next ship went “boom!” and the next ship and the next ship and the whole city exploded. It was probably the biggest explosion in the history of the United States.

HSV: Okay, let’s get back to San Francisco … room #6, Eric Swanson …

RJ: Oh yeah. So I was admiring this ship model, the big one, Preussen, which is German for “Prussian”. All of their ships were named beginning with the letter “p” because the man who owned that ship line, his name was Flying P Ryan. Pamir, Pisagua, Placilla, Ponape, Priwall, Parma ….

[waitress comes; eating slow …]

I’m the slowest driver in West Marin.

CJ: You should get a belt buckle for that.

RJ: Yeah. I should write a letter to the highway patrol.

HSV: So back to Eric Swanson, room #6.

RJ: He told me how to get to the museum and I went to the museum. I’m admiring the ship. He made the masts out of pool cues! The taper is perfect like a mast for the model.

[to waitress] I haven’t had memorable meal like this since 1956. Of course I have a bad memory.

HSV: Okay, back to San Francisco. I asked you what brought you here, why’d you stay, and why’d you like San Francisco?

RJ: The only thing I like about San Francisco is the Balclutha and the San Francisco Maritime Museum.

CJ: What about North Beach?

RJ: I had some interesting times in North Beach. One time John Perry Barlow and Bob Weir and I walked into a place in the corner …

HSV: Carol Doda’s — titty bar?

RJ: Yeah. Now she wasn’t there, we didn’t meet Carol but they were having a show and we were sitting there …

[waitress comes with coffee … we say “Thank you, Marie” “Thank you, SWEET Marie” … did you know Bob Dylan wrote a song called that?

RJ: No, she’s too young to know that. [laughter all around].

CJ: You know how to compliment a lady.

RJ: Okay, yeah, so I’m looking at the model for about an hour, there’s all these little tiny men climbing in the rigging, and there’s chicken-winged pigs up around the forward deck, and there’s laundry blowing up there on the fullsail head – the sailors wash their own clothes. They don’t see land for nearly 4 month. 100 days. And there’s all this stuff going on the ship, it tells a whole story.

So I’m there staring at the ship, and all of a sudden I can feel someone behind me, he’s looking over my shoulder right near me, and he says, “You like it?” It was Karl Kortum, the man who started the museum, the curator, and he’s an old sailor too. And I said, “Yeah!” He says, “You wanna come to the work party?” “Sure!” He says, “Okay” and I told him where I was staying at my cousin’s, who lived on Lake Street.

They picked me up at my cousin’s house the next morning in a truck and we went over to Sausalito to take the bowsprit and the main boards and the trail boards and the upper part of the cut water off of an old wooden 4-masted schooner, the Commerce, the was layin’ half-sunk in the mud in a shipyard in Sausalito. And I brought my guitar along, just in case. You know, in those days I was going to be a troubadour. I was under the influence.

HSV: You were gonna be … you coulda been somebody.

RJ: I coulda been a musician. I coulda been a contender …

HSV: Marlon Brando in On the Waterfront …

RJ: The one thing that made me real jealous of Bob Dylan, he got to hang out with Marlon Brando.

HSV: So did Steve Brown [featured on cover of Edition #3 “Bringin’ Love — and Music — to Vietnam”].

RJ: He did? Steve never even told me that.

HSV: Yep, at the Kezar Stadium in ’75 with Bob Dylan, Neil Young, and Marlon Brando was there too at the SNACK Benefit Concert (aka “SF Needs Athletics, Culture & Kicks”)

RJ: What a rat! [change of subject]

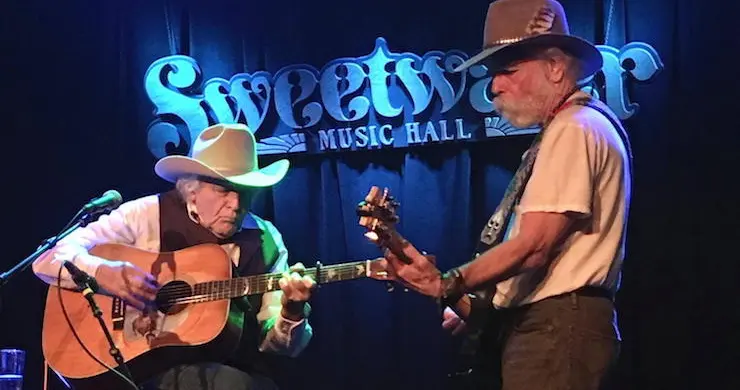

You know, I did a cowboy song with Bob [Weir], I call him “Roberto” so he knows who it is. Bob Weird. I was doing this cowboy song that Bob wrote and he wanted be to contribute something, but I couldn’t contribute anything in his language cuz I don’t think in that language, or even translate anything into Bob’s language.

So he’s going on with these words and stuff, and it don’t sound like any cowboy song I ever heard, but that’s Bob. He’s his own guy. I was just contributing noise in the background, like [whistles] “Hey! Hey cow! Hey [whistle] Hey cow [whistle]!” and they recorded that and they put it on the record and they paid me.

About six months later, I hadn’t gotten a copy of the record and I called Bob and I said, “Hey Bob, is the record out?” He said, “Yeah, it’s out.” I said, “Could you possibly send me a copy?” He says, “Sure Jack. Do you have a turntable?” “Oh you mean it’s out on vinyl?” “Yeah, it’s out on vinyl.” “No, I don’t have a turntable but I’ll buy one. Send me a copy of the record.” “Okay, I’ll send it to you.”

Of course, it’s also out on CD that I could’ve gotten. But six months went by, he’d forgot. He didn’t send the record. I called him again, six months later — that was about six months ago. I said, “Uh, Bob, could you send me a copy of our tune, you know, the cowboy song?” “Oh sure. Do you have a turntable?” “No I don’t have one but I’ll buy one. I’d love to hear it.”

photo: Gary Lambert

HSV: What’s the name of the song?

RJ: “Ki-Yi Bossie” … I thought Bossie meant a milk cow but he’s addressing the cattle as Bossie in this song. I didn’t contribute very much. I’m grateful. The gave me a credit in the liner notes. It says, “Ramblin’ Jack and the Ramblin’ Jackanacle Chorus”.

HSV: Bobby Weir’s been a big connection for you in the Bay Area. How did you meet Bobby — and he’s an admirer of yours as well, certainly.

RJ: Chesley Milliken, who was my manager from back in L.A. before I came up here. And when I moved up here, Chesley had moved up here too and he was involved with the Dead. His office was in 1330 Lincoln Avenue. I call it the skyscraper cuz they had an elevator in there — three stories high. The ground floor, Franki Weir had her kind of travel agency for booking tickets for musicians, and it was called Fly By Night Travel. And then Chesley’s office for booking musicians was called Out of Town Tours.

So if I wanted to find out about some tours I’d go to 1330 Lincoln Avenue and I had mail, there was a thing that said, “Jerry Garcia, Bob Weir, Chesley Milliken …” everybody’s name … and “Jack Elliott”. I was right up there with ’em. I’d get two fan letters and four bills every month or so. And one day I got a bill from Sausalito Moving and Storage, I had separated from my wife, Martha, Iona’s mother, in Santa Cruz, and I left some of my stuff: saddle, automotive tools, sleeping bag, some hats, a pair of chaps that I made. I made one pair. It’s the first time I ever did that.

HSV: Those leather suspenders you have on right now are great!

RJ: These are not mine, these are Larry Mayham’s. I stole them from Larry. Naw, Larry gave ’em to me. They’re the only things that hold my pants up since I lost my ass in the music business. [laughter] Belts do not work!

HSV: Back to the story …

RJ: So we’re in the titty bar, and this girl gets up on the stage and she looks down in the front row and there’s John and me and Bob, waiting for something to happen. She looks down and recognizes Bob and she’s a Grateful Dead fan and she got all embarrassed and she couldn’t perform. She left the stage trembling, poor girl, she couldn’t do her thing in front of Bob Weir, like, “That’s Bob!” It took away her whole thing, the magic that we think we have when we go onstage, you better have it.

I don’t have a lot of secrets to my success but when I get ready to go onstage in a theater and there’s a sound guy and a stage hand and there’s this curtain, you know, and I’m waitin’ and then the turns to me and says, “You ready?” And I go, “No” — and then I go out. And somewhere between him and the microphone, I get ready

But I never feel ready when I’m there waiting. That’s too nervous.

I told Kris Kristofferson, cuz in Texas they have a thing down there called South by Southwest? There is no such compass point. It’s Southwest by South. They got it bass-ackwards. But, you know, they’re 120 miles from any saltwater so it doesn’t matter. South by Southwest — nobody knows where anything is anymore.

Anyhoo, I was performing there and I went to see Kris Kristofferson. He was getting ready to do a show and we were hanging out in his dressing room. Now you shouldn’t talk to an artist before they perform, but Kris, we have kind of a friendship goin’ and he was chattin’ away with me and I’m chattin’ away with him, and all of a sudden Kris says, “Ah, Jack, I’m gettin’ nervous, I’m getting’ nervous.” I said, “Kris, do not get nervous!” I said, “The one thing I hate most is falling asleep onstage.” And he laughed! He got the joke. He laughed and he went out there and he did a great show because he relaxed and he forgot to be nervous.

Waitress: Do you want more coffee?

RJ: A little bit. Just one centimeter, thank you.

Waitress: Dessert?

RJ: No thanks, I’m not a dessert person. In fact, I hardly ever eat food.

HSV: You know who this is?

Waitress: He looks familiar …

HSV: Ramblin’ Jack Elliott …

RJ: No, no, no. Don’t get familiar with me. I’m the unknown quotient. You’ll hear about me after I’m dead. I don’t mind getting famous after I’m dead but I hope I don’t have to jump off the bridge to get dead. I want to live out my life to 235 years, cuz that means I can’t be famous while I’m alive. I don’t need the publicity.

HSV: You’re gonna be on the cover of my magazine. What is it that you love about the Bay Area? Why do you stay here?

RJ: Well, originally, I was close to the San Francisco Airport so I could get to gigs. Most of the gigs I play aren’t here, they’re far away and I have to fly. But I’m totally burned out on flying. I know how to fly a plane but I do not know how to walk through a goddamn airport.

HSV: But you stay here. If you could live anywhere else, would you?

RJ: Yeah, I think I’d rather live in Argentina or Arkansas or Alaska — anyplace beginning with A so I can start over again. I don’t like civilization, especially under the new regime.

HSV: Don’t you love the Bay Area because you’ve got Bonnie Raitt, Weir, all of them, right? There’s a reason that Jerry Garcia was here.

RJ: I got Roy Rogers and Bob Weir and Peter Rowan.

HSV: Off the top of your head, what’s one of your favorite moments singing in front of a crowd? What was one of your happiest, most beautiful moments, where your heart beamed and you were happy?

RJ: I’ve had a lot of those and I can’t remember hardly any of ’em. But I do remember the worst one: The only competition was Neil Armstrong setting his foot on the moon in 1969 at the same moment that I set my foot at the microphone in Newport Folk Festival where 18,000 people paid a 100 dollars to see me and they could’ve stayed home and watched Neil on TV.

I was watching him on TV up until about 10 seconds before I went onstage. And George Wein, who’s the owner and boss at Newport, was announcing me and he turned around and looked at me and he says, “Come on, Jack” and I turned around and pointed at the TV set and said, “Wait, I can’t, wait, this is history” and he says, “C’mon Jack, this is Newport”. The worst time I had was trying to entertain these 18,000 people while Neil Armstrong stepped foot on the moon.

It started raining, and I remember there were 10 rungs on the ladder and I measured the speed that he was comin’ down the ladder, so I’m walkin’ the same speed that he’s walkin’ so that I [slows speech] got-to-the-mi-cro-phone, pointed to the moon, and said, “He’s just stepping on the moon … now!” like I could see it with my naked eye, which is bullshit. But it was true and everybody laughed. I got a big laugh. And then I started playing “San Francisco Bay Blues”:

“I got the blues from my baby left me by the San Francisco Bay, ocean liner she gone so far away, didn’t mean to treat her so bad, she was the best gal I ever had, said goodbye, likely made me cry, I wanna lay down and die, haven’t got a nickel, ain’t got a lousy dime, if she don’t come back, think I’m gonna lose my mind, ever come back to stay, gonna be a brand new day, walkin’ with my baby down by the San Francisco Bay.”

CJ: Have you ever sat on the dock of the bay?

RJ: Never have sat on the dock of the bay but you know the guy that makes the Grammies. The guy that makes the Grammies doesn’t live in Hollywood he lives in the mountains of Colorado with his wife, who grew up on a dairy farm and she’s a Scorpio girl and she likes to call me up talk on the phone for hours. They’re good friends of mine. I’ve hung out with them a couple of times and they made me sleep in their bed and they slept downstairs on a couch while I slept in a bed at their house. And they entertained me with a record with “Sittin’ on the Dock of the Bay”, drinkin’ good whiskey and smoking good pot and petting their kitty cat.

HSV: What about the Golden Gate Bridge?

RJ: I LOVE the Golden Gate Bridge, and I’ve met …

HSV: You’ve met everyone!

RJ: Yeah, I’ve met everybody. [laughs]. I met the man who was the flight engineer in that airplane that you see in those postcards, that airplane flying over the bridge and there’s no roadway yet? 1937. I had dinner with him. He lives in Idaho.

HSV: How did you work that out?

RJ: I didn’t work it out. I don’t work anything out. Shit happens. All the greatest things that have happened to me in my life were not the result of any kind of enterprise, planning, wishing, praying, hoping or thinking.

CJ: That’s a very important part. It just was your intuition.

RJ: I was just in the right place at the right time. If I try to make things happen it doesn’t work.

HSV: What’s that Lennon quote: “Life’s what happens when you’re busy making plans” something like that. You ever meet John Lennon?

RJ: No, I never did meet John. I met Casey Tibbs — the greatest bronc rider that ever lived! He was from Fort Pierre, South Dakota. I wanted to learn how to ride buckin’ horses.

CJ: We’ve gotten way off track. Where were we? Oh yeah, the worst musical experience …

RJ: Oh yeah! When they set foot on the moon. There was some disturbance in the crowd, some noise out there and it was raining and I remember, I took my hat off cuz I had a roof over my head. The guitar’s not gettin’ wet, I’m not gettin’ wet, but they’re gettin’ wet. I felt sorry for them.

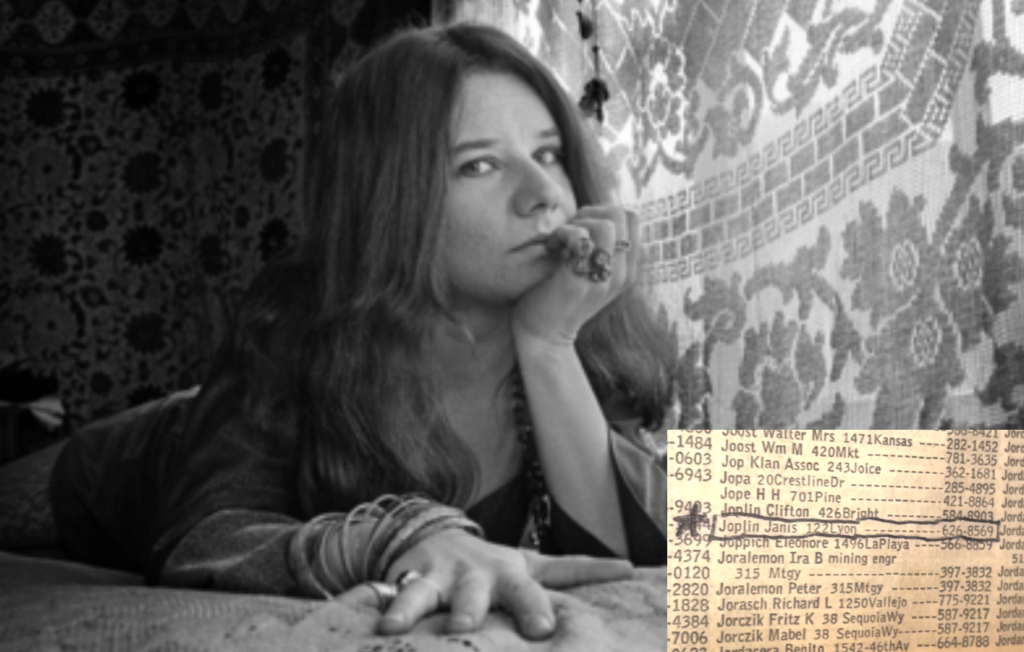

So I took my hat off and I had these Hopi indian rain beads around my neck and I took ’em off and I said a prayer that it would stop raining. But I don’t speak Hopi and I don’t know the right thing to say. It didn’t work. It kept raining. And then some people that were eager were pushing and leaning on a wooden fence and “crash!” and then there were about 95 press photographers with flashes going off on their cameras, taking my picture, and I never like that. I forget the words to songs. So then I started cussin’ at ’em. Kris Kristofferson was there. It was his first time in Newport. It was Johnny Cash’s first time in Newport, and Pearl, too –Janis Joplin.

I danced with her later that evening. But the guy’s steppin’ foot on the moon and I’m trying to entertain 18,000 people.

HSV: Neil Armstrong stole your thunder!

RJ: Yeah, I’m afraid he did!

HSV: So, Janis Joplin — you danced with her after that gig in Newport?

RJ: Yeah, she gave me a sip of her Southern Comfort. Yuck! Too sweet.

HSV: How was Janis? Was she a good dancer?

RJ: Yeah, she was a good dancer. Better than me!

HSV: Did you make out with her?

RJ: No! I just met her. I’m kinda shy.

HSV: How’d you do in school?

RJ: Not too good. I got Cs and Ds. I got one A, one F, three Ds … I’m not a very good student.

HSV: If you were going to recommend a book to someone, what would that be?

RJ: Sailing Alone Around the World by Captain Joshua Slocum. He sailed from 1892 to 1895. The first person to ever go around the world alone.

HSV: What’s your most favorite sound?

RJ: I like the sound of a Cummins diesel revvin’ about 1500 RPM.

HSV: Alright. And what’s your least favorite sound?

RJ: The sound of waitresses whispering while I’m trying to do a sound check. I love the sound of a steam locomotive. The first time Muddy Waters ever played a guitar in England, I got some of his perspiration on my face. I was sittin’ on the floor in front of him in the front row, upstairs at the Blues and Barrelhouse Club run by Cyril Davies and Alexis Korner, two Englishman who loved American blues guitar playing. They started listening to records of guys like Blind Willie Johnson and Lead Belly, Brownie McGhee and Sonny Terry and Blind Lemon Jefferson — all those guys.

HSV: Big Bill Broonzy?

RJ: Big Bill Broonzy! I met Big Bill Broonzy in that same club the first time he ever came to England.

HSV: How old were you?

RJ: 25.

HSV: So you had Muddy Waters’ sweat on your face …

RJ: Yeah, and I opened for Muddy for a concert about 15 years later in Portland for a bunch of white people, Blues lovers. And because I’m not black, they weren’t listening to me at all, and I didn’t see Muddy in the dressing room because he wasn’t there yet. I had to go on before he arrived. But he arrived and they saw how rude they were to me. I was so pissed off at these white people that I didn’t even stick around to listen to Muddy.

A woman, 20 years later, a gal who’s a journalist, she wrote for Marin’s Pacific Sun paper, I don’t remember her name but she told me 20 years later that she was at that concert. And after I left the building, Muddy came out and they all clapped, and he waited for them to stop clapping, and then he said, “Before I start I wanna tell you people that you were very rude to Jack Elliott. He’s a very important folk singer.” That’s what Muddy said.

His original name was McKinley Morganfield. I didn’t know this but somebody told me last night on the phone that Sister Rosetta Tharpe, who was a big friend of Bob Dylan’s when he was a kid, and I met her once in New York, Sister Rosetta Tharpe was Muddy Waters’ sister! She has never been nominated or anything at the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame.

I was at the first Rock and Roll Hall of Fame with Arlo Guthrie to receive an award for Woody posthumously. Mick Jagger was there and I said hello to him. Bob Dylan was there, Mr. Love was there of the Beach Boys. Bob was very critical of him cuz the Beach Boys acted like assholes.

I was there due to a late arrival due to fog. Joe Henry was a kid at the time working for Sire record company at the time that paid for my ticket to come to this thing, and he was the only kid working for the record company who knew what Ramblin’ Jack’s supposed to look like. So they sent him down with a limo to pick me up. My daughter Aiyana was with me. We were about 45 minutes late. Joe Henry introduced himself and said, “Ramblin’ Jack, come with me, we’ve got a limo, we’re late.” We zoomed in to New York to the Waldorf-Astoria hotel. I saw a couple of black musicians in tuxedos. They were there to receive awards. I didn’t know who they were, and they said “Hey Ramblin’ Jack!” I was wearing a red and black lumberjack shirt and a dirty Stetson hat, and I’m with my daughter, and the bags went up to the room, and we went “zwooop” right in and there was Alan Lomax, Pete Seger and his wife, and Arlo Guthrie and his wife. Arlo had already received the award for Woody posthumously, a half-hour earlier because I was late gettin’ there.

And then some fat guy who was the owner of the record company that paid for my ticket, came over to me smokin’ a cigar and said, “Too bad you were late” he was very shy, he could hardly even speak. I said, “Sorry.”

HSV: What would you like to say to Woody Guthrie right now?

RJ: He’s one of the only worthwhile people I’ve ever met.

One night I sang my favorite Woody Guthrie song, Hard Travelin’, and I was singing at a cowboy’s birthday party October 31, Halloween, and he was 1932 world champion steer wrestler and he was the corral boss at Siberon Dude Ranch when I was working up there trying to be a cowboy at the age of 16. Harry Tomkins, world champion. So I’m sitting there playing guitar, my Gretsch guitar, singing “Hard Travelin'” and everybody clapped and I said, “That song was written by Woody Guthrie, and the man standing near me who later was the president of the Rodeo Cowboy’s Association, and I had ridden a horse for him. He didn’t ask me to but it was like the announcer said that it was Bill Linderman but it was really me [laughs] and I didn’t make him look very good cuz I fell off in about three jumps. A black horse called “Why Bar Me”.

Anyway I was playing “Hard Travelin'” and I said, “That song was written by Woody Guthrie.” And Bill said, “That IWW son of a bitch!” cuz he thought Woody was a Communist. But Bill was a great rodeo cowboy, he was one of my heroes. So I didn’t say anything. He could’ve killed me.

HSV: What is one of the most outstanding things that Woody taught you, like a line he said to you, or a voice of reason, or advice?

RJ: There’s a line that Woody said: “Just play two chords. Any more than two chords is showin’ off.”

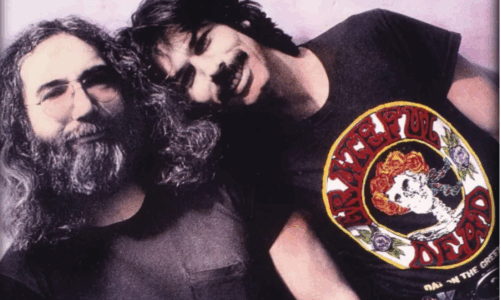

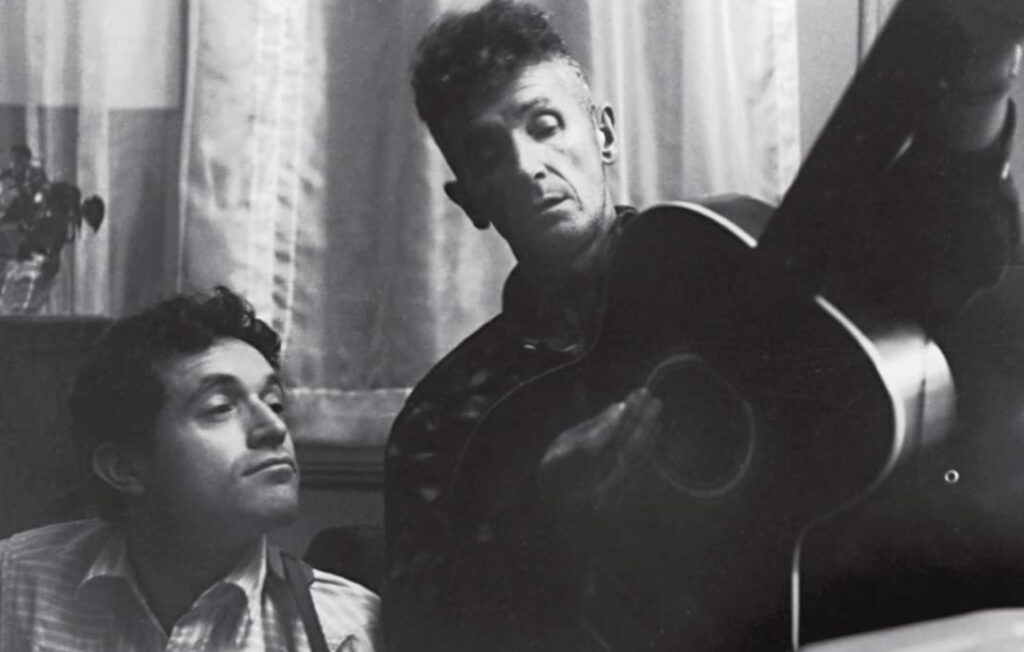

HSV: Do you remember your own personal time hanging out with Woody at his house, playing music, joking around — there’s a picture of you two smoking cigarettes and it’s like you’re having a good ol’ time.

RJ: Yeah, he liked to laugh. He had corny jokes. He had books full of corny jokes. He had a head full of those corny jokes [laughs]. I don’t remember any of ’em. Oh, wait, okay. We’d drink a beer in a bar, he’d take a sip and he’d say, “Good for your wife’s kidneys.”

He whipped a 20 dollar bill out of his shirt pocket and threw it out of a taxicab window, I didn’t think we were that wealthy. He just had no use for money, no respect. I remember bein’ in a bar the first time I was ever over in London, England, the first year I was there. I was in a pub and I met some actor who is probably famous but I didn’t know his name, but he’d been in America one time and he said Woody was marching in a parade in New York and I think it was May Day, and the Communists have a big deal. Woody was walkin’ and probably had his guitar with him, probably in New York City, and this actor told me he heard somebody say, “Who’s that bum with the guitar?” And the actor said he said, “That’s Woody Guthrie and he can march anywhere he wants!” And that was my arrival in England, and I thought, “I’m gonna have a good time here.”

HSV: You’ve been through a lot of generations, we’re obviously in a weird moment in the history of America with this president clown at the wheel …

RJ: Ooooweee!

HSV: What was your favorite era? What were some of the happier times?

RJ: I liked Roosevelt.

Of course, there was that time I was thrown out of a school in Connecticut for trying to convert their paint Shetland pony into a bareback bronc. I was about 14 years old. Cherry Lawn School, it was owned by a woman named Dr. Christina Stahl von Holstein Boguslavsky. Her husband Boguslavsky was Russian, she was Swedish. We called all our teachers by their first name. One of my heroes in school, I hope he’s still alive, was a kid who was about 5 years my senior, he was about 19 years old and I was about 14 and he smoked a pipe, and he had a face like a St. Bernard dog. He grew up on the Smith College campus. His father was the dean at Smith College. He owned a .45 caliber six-shooter, and he had a pony and he could shoot a target in a tree at a gallup, and would hop freight trains up to Maine where he’d built a cabin in the woods where the windows were made out of beer bottles cemented in place. One day he hopped a freight and he didn’t go to Maine, he ended up changing trains Omaha, Nebraska and then got another freight and ended up in Montana and got a job workin’ on a ranch when he was about 14.

Then he came home again, got a job working as a gunsmith in the Marlon Arms Factory. Then he lied about his age and joined the Navy and he became an aviation ordinance man in an aircraft carrier, underage, he was 17. He was arming the machine guns in these fighter planes on an aircraft carrier. And later he got out of the navy in San Diego and got a job as a cowboy on an Arabian horse ranch in Escondido, California. And I was hearing about that and it was about 1946, I was 15 years old.

In ’47, I was back in Brooklyn and I ran away from home with these two poets who were from Cherry Lawn School with Christina Stahl von Holstein Boguslovsky and her husband, and we decided to run away from home. We hitchhiked across the George Washington Bridge, and a truck stopped and he said he only had room for one, and I left them and went.

I’ve always felt very, very bad about that.

It was two guys, Don Finkle, a poet who later got a job teaching poetry at a university in St Louis, Missouri. And the other poet was a guy by the name of Carl Margulies, and I don’t know whatever happened to Carl. I think both Don and Carl died, and they probably never forgave me.

HSV: What would you like to be remembered for? You’ll obviously always remember Woody forever …

RJ: That’s a big, big, big, big, big question.

When I was living with the Guthries in Brooklyn, the apartment house was called “Beach Haven Apartments.” Woody called it “Bitch Heaven”. It was owned by Donald Trump’s father, and you couldn’t be Chinese or Negro to get a room there. I don’t remember Woody ever talking about it to me at all. He wrote a song about “old man Trump” but I don’t remember him talking to me about it at all.

HSV: Back to what you’d like to be remembered for … you’re funny. One of the best things about you is the way you love to laugh.

RJ: Yeah, I like to laugh.

HSV: If somebody was talking about you, “Oh that Ramblin’ Jack Elliott…” In the way that you talk about Woody, what would you want someone to say and remember about you?

RJ: Woody would love to reminisce about his adventures in WWII washing dishes on a ship and being torpedoed a couple of times and got his guitar, mandolin, fiddle, capos and picks and strings into the lifeboat. Cisco Houston and his old Buddy Jimmy Longing, three of them were buddies in the Merchant Marines. Got torpedoed by a German U-boat twice. He wrote on his fiddle with a wood-burning set saying, “Woody Guthrie, 1944, S.S. William B. Travis, S.S. sea porpoise. USA, NMU, CI0, Drunk once, Sunk twice.”

HSV: How do you remember all of these details?

RJ: “Goddamn, low down, no good son of a mother fuckin’ ass lookin’ shit eatin’ piss complected pupilated pimple on the prick of progress poor mongerin’ bitch bastard jerk”.

A string broke in the recording studio on a mandolin, and the whole rest of the record was cussing. I learned that from Tom Paley. He memorized it from the record. I actually heard the original record. That’s poetry.

CJ: One thing about Jack that a lot of people would admire and remember is that you are an amazing repository of facts. Just incredible amounts of information that you’ve preserved in your head and access like some database.

HSV: Except we couldn’t find Marin Joe’s today. [laughter] When you wake up in the morning, you want your coffee, yes, but what do you think about? You want to play guitar, read a book, go for a walk, what do you want to do?

RJ: I never play guitar. I should. I really need to practice. I’m forgetting how to play. I remember but my fingers aren’t.

How’d you feel about Dylan back in the ’60s?

I liked him. I was charmed by the fact that he saw fit to copy me. They say imitation is the sincerest form of flattery, so I couldn’t get mad at him. He became sorta like my sidekick. He was there all the time. Even he reminded me of my one time, after he was very famous.

HSV: What’s one of your favorite moments singing in front of a crowd over the years?

RJ: I’ve had a lot of those. I do remember the worst one: Neil Armstrong was setting his foot on the moon in 1969 at the same moment I set my foot at the microphone in Newport Folk Festival, where 18,000 people paid a 100 dollars to see me, and it was raining. I remember I measured the speed Neil was comin’ down the ladder, and I’m walkin’ the same speed that he’s walkin’ so that I [slows speech] got-to-the-mi-cro-phone, pointed to the moon, and said, “He’s just stepping on the moon … now!” like I could see it with my naked eye, which was bullshit. But it was true and everybody laughed. And then I started playing “San Francisco Bay Blues”.