by Linda Kelly

We at Haight Street Voice are eternally grateful to you, Steve Brown. Thank you for your service — and your epic sense of humor. LOVE & LAUGHTER!

________________________________________________________________

“Never give up seeking and following the paths that create and provide positive purpose in your life and benefit the happiness of others.”

— 2017 Summer of Love wish from veteran Steve Brown

With all the media attention on the Summer of Love, we wrangled with ways to make this third edition of HSV unique somehow, to keep it real. And it doesn’t get more real than Steve Brown, who was serving in Vietnam during the Summer of Love. After all, the incredible beauty that blossomed during the summer of ‘67 never would have occurred without the radical contrast of the darkness that was going on in that horrific war overseas.

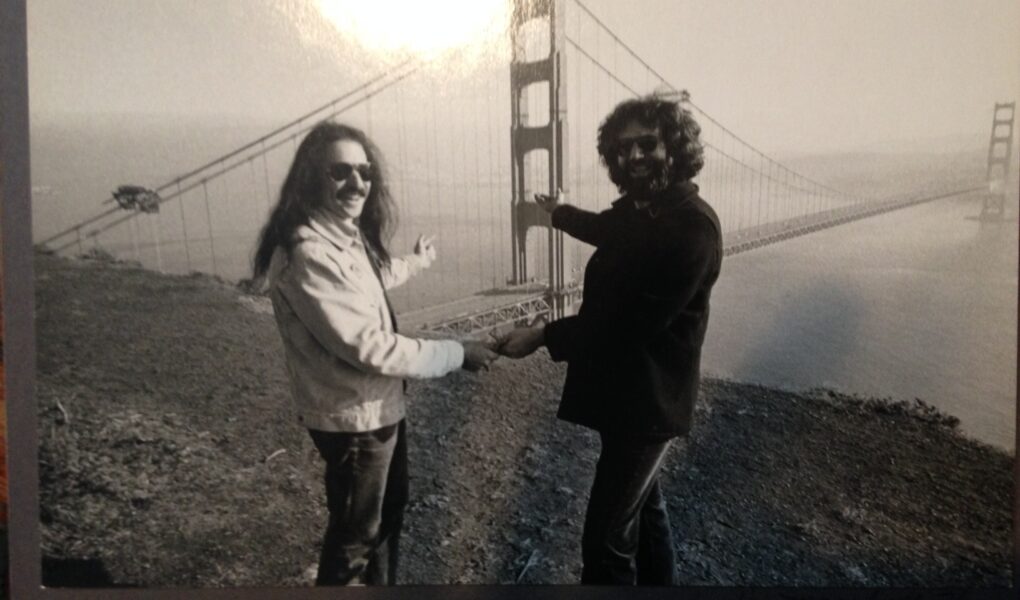

Seventy-two-years young, Steve Brown was born and raised in San Francisco with a passion for music, nature, surfing, history, filmmaking — and sharing it all. After years in radio and the record industry, he wound up working closely with Jerry Garcia and Grateful Dead Records in the early ‘70s. But it’s the story of what led up to that time that we want to share with you here. The following is excerpted from an interview with Steve that we covered along with BBC Radio Wales — where, even in a teeny little town called Penarth, they experienced the Summer of Love in l967 all the way across the pond.

We love you and everything you are — take it away, Steve!

Chelsea Dickenson: Tell me about you and your connection to the Summer of Love.

Steve Brown: Well, this is a really interesting kind of thing because what wound up happening is I was finding out that I was vulnerable to be drafted and go to Vietnam. This is back in ’65. So they said, “Well, if you’re married, you won’t have to necessarily be drafted.” So my girlfriend and I got married and, in fact, a few months later they said, “Well, even if you’re married you can get drafted.” They were getting hard up to feed this war that they had going over there.

Luckily I was able to get some connections through my dad to go to Treasure Island here in the San Francisco Bay, and be able to talk to a commander there who asked, “What’s your background.” I had been in radio up to that point, and the music and entertainment business, and they said, “We have a recording studio in San Diego, the guy’s going to be leaving, it’s the public information office. And what they do is they record all the music for all the ships out in West Pac Fleet, out in Vietnam in the Pacific. I said, “Yeah! I could do that.” [laughs] Recording studio, making dubs, basically, of all these reel-to-reel tapes and a menu of all the different music.

So as the Summer of Love approached, I had to sign up for Active Duty and go down to San Diego. This is 1967. I was still able to come home on the weekends. I’d been at the Be-In, and I was ready to continue in that kind of lifestyle, but no, April came and I had to go to Active Duty. So as the Summer of Love approached, I found myself in San Diego but flying home on the weekends to go to the Fillmore, see the first three bands, the first three sets, and then jam over to the Avalon and see the other three bands that were playing over there, and visit with friends, get high, get back on a PSA plane and fly back to San Diego just in time to do this late-night radio “Until Midnight” on Sunday night, and start up the rest of the week working in the recording studio. And came back on the weekends to go to Mt. Tamalpais in Marin where they had two days of these Summer of Love type of events, which was in fact put on by a local radio station and they had the Byrds, Country Joe & the Fish, the Airplane, 5th Dimension ….

I would come back on the weekends and keep touch with the culture that I was more familiar with than, you know, the US Navy. But luckily, I shared the building with an art studio where my friend, who went to San Mateo college here and was an art major, and he was doing all the art that the Navy needed for posters. And, of course, he started making them psychedelic [laughs], and started making weird floats for their parades. That’s probably because he had a big bag of Owsley White Lightning, and it was the early white ones, which were like 250 ml! He would be dancing with the walls.

KPRI FM radio “O.B. Jetty Show, March 1968, San Diego.

Anyway, it turned out that though I thought I was going to spend a lot of my Summer of Love going back and forth to San Francisco, they realized that I had been moonlighting on this radio show. So I quickly put somebody else in my place, but they said, “You know what? We’re going to send you with the Admiral’s flag staff over to Vietnam to work with film crews” — doing recording for their films they were doing for the Navy operations over there, and also to be able to do recordings with people, personnel, the military, for radio stations for their home towns, and also take still pictures for Stars & Stripes magazine, the military magazine.

So I’m sent — right before the Monterey Pop Festival happens — to Vietnam. They flew us over there with the flagstaff onto a ship, the St. Paul, in the Philippines. At that point I had, luckily, been able to make, because I had the reel-to-reel recorder, a bunch of 5-inch reel tapes that had the new Jimi Hendrix album on it, it had Sergeant Pepper, it had Grateful Dead, it had Jefferson Airplane. I had the headphones that came with it. And I’d wind up finding these guys who were over there who were also missing out on the Summer of Love back home, and I’d say, “Hey, listen to this!” You’d put the headphones on them, put that tape on and, them being off on liberty, being able to have things to smoke, and listen to what they were missing over there.

I felt kind of like a missionary. I was over there spreading the Summer of Love to our soldiers in Vietnam. It was kind of a little bit like Good Morning, Vietnam syndrome that Robin Williams was able to portray. And literally I kind of was because I was running a recording studio to send this music out, and it would go to the ships, and the ships would have an entertainment system where there were speakers in all the different compartments of the ship and it had four channels you could dial in: country-western, rock and roll, comedy, classical, whatever — and I just wound up air-checking my radio show because they had all the far-out, new shit on that became the most popular tape that I sent out over there.

So somehow my connection with the Summer of Love was able to journey over all the way to Vietnam and still kind of keep the juice alive, as it were, of that feeling. It was funny because some of the ships would be based out of San Francisco so when they home port in San Francisco they would have stories about going to the Fillmore and going to the Avalon and how cool the scene was in the Haight-Ashbury and all this kind of stuff. So there was a kind of a nice feeling that I wasn’t that far from home when I was all the way across the Pacific in this land where people were waging war. It made it almost this kind of, like I said, missionary journey, which really made it nice.

One time I was on this supply ship and I’m walking along with this film crew, and all of a sudden I hear my voice coming out of the PA system, the speaker system, on one of my radio shows. So to hear yourself, very surreal, out of body experience, you know, to hear yourself on another ship all the way over there in Vietnam. That kind of stuff was, you know, memorable. [laughs]

CD: It’s really interesting because I have a sense, and you may have your own opinion on this, but the reason for the Summer of Love was that people weren’t happy with the war, and there was that feeling of love, peace — what are we doing? But you were a part of the war, essentially. So how was that for you to be part of something like that, disconnected from a movement that you also felt close to?

SB: Well, I never disconnected myself from it. That was the secret. I was still secretly, obviously — not secretly, I was pretty vocal about it, against anything to do with this ridiculous war that was going on over there. And with the counterculture scene that was back here was manifesting as far as a new way to help other humans living a peaceful and happy and healthy life was something that I was still promoting while I was over there. Every time that I would meet with people who knew about what was going on over here, I wouldn’t hesitate on trying to make sure they knew that that’s who I was about and what I believed.

I got in trouble for it a few times, like, “Get a haircut, Brown!” So I just let my nails grow long! It really wasn’t very much of a secret, believe me. there were a lot of guys over there, and women too, that were part of the nursing thing, that really weren’t trying to be promoting war or wanting to make it something that was going to be something that they thought was right. They were really only trying to help get everybody home safe, one way or another. So I felt I wasn’t really doing the wrong thing to be over there. I was doing the best I could with the situation being over there. And I didn’t hesitate. There were peace signs on the lockers in the ships. There were people with tattoos and stuff.

USS St. Paul, July 1967 Vietnam

When you went on liberty and you went to these clubs in the Philippines in Subic Bay or Japan or Singapore, they were playing rock and roll from the United States. They were playing the songs that we all were hearing on Armed Forces Radio or on the radio stations that were back home. Everybody was getting a taste of what they were missing even when they were all the way over there in a war. And people played in bands in Vietnam, the soldiers themselves. As a matter of fact, one of the documentaries I did was called “Song of Vietnam”, which were songs written by the soldiers over there. And believe me, most of them were against the war and for a better world and a better life. It was interesting to hear some of these songs initially when I got them because they were done by guys that were right in the middle of combat, but they had a guitar, or when they got back to the base, wrote these songs and recorded them. So it was interesting to be over there.

So, again, my Summer of Love was really spent at war, and so it makes my story a little different probably than most people who stayed back here cruising the Haight or going to the park, which of course when I came back I dove right back into and became part of, and went on to work for the Grateful Dead. And I even told people when I was in Vietnam, and it was funny because I had no real reason to say it or to believe it, but I’d say, “You know, when I get back I’m gonna go work for the Grateful Dead.” Be careful what you wish for! It happened!

The experience made me appreciate what the Summer of Love meant, by having to go over there. On one hand as kind of a missionary kind of mode to try and spread what I thought was the real deal as to what was going on back here, and help people feel better about it, or understand it more. But I also had to miss out on being physically here with it. But I kinda took it with me and spread it as best I could.

CD: You talk about when you came back — when was that?

SB: I got off the ship December 1968 and was able to get right back into radio, and from there got into the record business, and from there, the Grateful Dead record company by 1972 when we started that.

In 1968, like I said before, before I had to go for a second tour over there to Vietnam I was able to spend a lot of time up here, and I still had that recorder. So I’d go to Winterland to record Cream one night, run into a friend who’d say, “Hey, you know the Dead are going to play on Haight Street tomorrow.” And I was like, “Oh god, how much tape do I have left?” And “How much battery power is in here? I’m gonna be there at noon.” And I took my Navy camera that I’d been using in Vietnam and put some actual Navy film in it and put some Navy tape on there, and I recorded the Dead on Haight Street and took some pictures. So it was like, “Thank you taxpayers of America!” Military money put to good use!

I didn’t let go. I kept keeping my foot in the door the whole time. I really didn’t want to have to give up what I knew was a new culture manifesting itself out of my hometown, San Francisco.

CD: Were you aware of that at the time, that this was not just a trend going on in your City?

SB: The media made it kind of trendy, but in fact I knew what the real-deal was because I was there at the beginning of it. I used to go down as a teenager to North Beach and see the Beatniks in the clubs down there, reading poetry and people playing music, making jazz, and to go read some of the books, go to City Lights and they had this amazing amount of poetry and things going on there.

So I was tuned into it, and then it started to morph into this scene where in the colleges, the younger generation that weren’t as old as some of the Beatnik guys had heard the new rock and roll stuff that came from the Beatles and the Rolling Stones, and everybody goes, “Hey, this sounds like more fun than that kind of downer Beatnik thing. Let’s rock and roll!” So all of a sudden everybody started putting on dances and join bands — “I wanna be like them! I wanna have a band!” I had friends and we had a band, “The Friendly Stranger”. So we were able to do that and go to California Hall and produce our own shows. There were all these little halls that you could rent around San Francisco, and have shows. It was fun!

I knew what the seed was to this culture, and it was based a lot on the music and the fact that … to feel good finally after the assassination of a young president who everybody thought was gonna change what our culture in America was gonna be, all reverted back to LBJ sending everybody to a war that he couldn’t really handle or stop, because it had already started, and fed that. And so I thought that this was a counter-balance. I believe it was a real deal, and I still do. I mean when the Diggers came out and fed people free food in the park, when people would share their space with others to be able to survive and such, and people would entertain each other in way that was fun and for free. I knew there was something more going on than what our parents had grown up with and been a part of. And maybe because we were more lucky to have the benefit of having been after World War II, where we grew up in kind of a more middle-class society that was able to give us the kind of freedom than our parents, who had gone through the Depression and had to go to World War II, and had suffered through. We were kind of blessed with a better scenario for a future life. And so when this came along, when the Beatles started playing, it was like “Okay, game changer!” This is where, you know, we’re gonna go with a new “us”.

So I believed in it all along — and I still do. And when I go to the 20th, 30th, 40th, and 50th anniversaries of it, I still feel it’s there, the essence of what we started way back when.

CD: How much do you think the power of the people was behind the end of the Vietnam war?

SB: Oh, a lot. I could show you film footage of hundreds of thousands of people marching down Geary Street in San Francisco and filling Golden Gate Park, Polo Field, more than even the Be-In. And I’m talking about seniors, parents, children, all of the hippies, all of the straight people, all of the gay people — anybody who had a consciousness on what was right about, you know, humanity and survival and helping each other, were there to protest this war. And it happened one, two, three, four times every year seemingly. But the big ones that happened around the country, people protesting at places like Kent State and getting shot for it — stuff like that, those things were just non-stop for the way things were gonna wind up. And everybody knew it. It was just a matter of time. We couldn’t keep going with something that was a losing proposition on a lot of levels — I’m not just talking about the 58,000 men who lost their lives, I’m talking about just the idea of going to another peoples’ country and killing them because you’re afraid the type of government might change, communism, which we were always afraid of. That was something that was inevitable is was gonna end, it was “how soon?” And these big protests made the difference. And, again, it was all those same people from the counterculture … PLUS. I mean a big plus. America saw that it was not right.

CD: How much of a political edge do you think there was to the counterculture movement?

SB: Political edge? I think people took advantage of the counterculture to use political agendas, rightfully so, and in some cases maybe for their own purpose, you know, of being radical or something to get out there and maybe create more of a violent reaction, which is ironic if you’re against war to begin with.

But the people who were genuinely peaceful about protesting I think won out, first of all, but I think the other part of it was that the political thing — it was just obviously wrong, morally and politically. And as much as people wanted to promote the political change, it was something that just organically had to happen. I don’t think the political thing had enough legs to stand on after a while. It was just wrong.

But they took advantage of it, the people who knew that they could organize all these people to — it’s important, actually, that they did because I think that that did push the fuel, fed the fire, as it were, and it kind of made it more important, maybe? I have to say they were right in wanting to organize and make this a political statement and a political movement — moratorium marches … all of that wouldn’t have happened without people who were really, really sincere about the political aspect of it. So it’s a good thing, not a bad thing. But there are those fringes and you see them Berkeley when somebody comes with a bad kind of idea to speak to people, and people react in a way that is more violent and worse than the person who’s gonna be speaking! So it makes it kind of wrong in that way, too. There is that border, there is that fine line at certain points, where political action and political activism and such has to work, and not hurt itself, you know?

HSV: When Trump got elected, we walked down Haight Street and asked people, “What do you think?” And they said it’s the best thing that ever happened, that it made everybody wake up and realize we’ve got to start hanging together and taking care of each other, cuz we’ve got a clown at the wheel. We thought that was really interesting. Thought that everyone would say it’s the worst thing that ever happened, but instead they said it’s good. It’s waking people up.

SB: Yeah. As you get older, you really find that sharing, and being able to help each other really is what it’s all about. And it’s a universal thing. That’s what America needs to do and what other countries who have the power to do so need to do to keep our home, the Earth, a viable place for everybody to live in.

God knows it’s turned an ugly corner as of late here, and I don’t know how it’s gonna manifest itself as far as pulling out of this car wreck that’s about to go off a cliff. I’m just really afraid that there’s been a big mistake happen and I’m hoping that at this point in time maybe a little bit of the feeling of the Summer of Love will creep into enough consciousness to be able to shine a light on something that can help make that change. So it’s good that it’s happening again, that there will be a consciousness about it, and remember why we had it — this cultural change to begin with. It’d be nice.

Steve Brown, today, 2017 ….

CD: I agree. I definitely agree.This program is about the fact that Summer of Love happened in San Francisco, and then there was a Love-In in Wales. What is a Love-In?

SB: Well, when the media got a hold of the Summer of Love, there was a kind of a, not only the hug each other, love each other, be kind to each other, respect each other feeling of love — consequently a “Love-In” — but there was also I think a little bit of a freedom of sexuality factor that probably some people read into it, or was promoted to make it a little more attractive as a media kind of focus — and/or just interpretation by normal folks thinking, “Oh it’s a Love-In! I can take my bra off” or one of those kind of feelings.

The kind of Love-In scenes that I remember specifically were outside of San Francisco. The ones in San Francisco weren’t really Love-Ins. If they were, they were being promoted by somebody who wasn’t really into what the real scene was. It was mainly somebody who’d either come to town and just call it a Love-In and see if you could get all these people together to have a Love-In.

I think the term went abroad to other countries with that tag on it, for better or for worse. Even in San Diego when we were down there they’d have Love-Ins at Balboa Park and I was almost kind of embarrassed by it myself, personally, because I always thought, yeah, it’s got that aspect to it of a wonderful feeling that people have being together. But on the other hand, it’s really almost something more than — love is just such a hard word to interpret I think sometimes as far as what it really, really means. I like to think of it in the positive always, but on the other hand I think that sometimes because they used it as that tag, maybe it’s kind of exploitive …

CD: I totally agree with what you’re saying, but a “Love-In” — what is that? Is that just people turning up and enjoying each other’s company. Is there poetry there, is there music?

SB: Oh yeah. All the above. A lot of the times it would be based around music. And if there was gonna be music being played in a formal sense of a stage and a band, equipment and all that, that’d be one thing. Sometimes it was just people. I remember in the San Diego ones, you had people just bringing their own instruments, and the little tribal groups gathering and entertaining themselves, dancing to the music with diaphanous gowns on and flowers in their hair and smoking joints and hugging each other, and just being really wonderful to each other and having a happy time in the sunshine of San Diego, which was great.

In San Francisco I think it was a little bit more serious in some ways about getting together to get something done. So there might be a fundraising event going on in regards to that. I know there were people who would have events that way and try to get a cause to be recognized and such. Which really didn’t make it so much a Love-In but more kind of a social event with some meaning, and some results, hopefully.

CD: Would they ever charge for a Love-In?

SB: No, I never heard of a Love-In being charged. If they did, that’s definitely the wrong people putting it on, or sponsoring it. [laughs]

No, that was the whole part of it. Maybe somebody had to get a permit for Balboa Park or Golden Gate Park to have any kind of big event. But a lot of time they were kind of underground, there’d be posters made and circulated through music stores, different head shops and such, that people would see it posted that there was gonna be this certain event at this certain time at this certain place — and the people would show up. They’d put on their Love-In finery, and bring their instruments and roll a bunch of fatties and roll down there and get high with their friends and enjoy it.

In cases like a military town like San Diego, you have to be careful because there was more of a police reaction to that kind of counterculture event. So you had to choose your timing and behavior a little more careful than you would, say, up here in Northern California and San Francisco.

CD: In Wales, there was a Love-In and it was arranged by a guy who normally did rock and roll dances, he told the media, he was privy to a lot of magazines, and probably was the only person in the whole town that read them, he learned all about it. He loved music. So he decided to put on a dance but call it a Love-In — but he charged. The hall itself didn’t serve alcohol, there probably wasn’t a lot of drugs. These were just young kids going to a rock and roll dance that was called a Love-In. is that a Love-In? [laughs]

SB: No! [laughs] That’s just a concert when you’re charging for it, you’re just cashing in on something culturally that was something other. And that’s what happened. It made that turn into the media. And when “Love-In” and “Summer of Love” and all those terms came out, it was like, “Oh no, now our scene is really gonna go down hill because they’ve kind of co-opted from us. And it feels like having something stolen from you, like “Oh no, wait! That was our scene. We don’t charge for this. We bring music and play for free.”

You’re right. There were a lot of promoters who had concerts already, or nightclubs, that would take advantage of this kind of thing. I think when we took the San Francisco sound and tried to get the seed planted in ’66 down there in San Diego — before I was even in the military, in active duty — we felt a little bit like we were part of a commercial kind of thing because we actually had to put it on at a place where people normally went to, where they would normally pay to get in to see something that was out of San Francisco that was this new music, that was these light shows, that was this whole way of dancing and enjoying the scene and such, and you’d probably get high in your car before going in.

And so it was a little bit like being one of those guys myself when we had to do that. But is was from Chet Helm’s crew of folks that we got the light show from and went down there with, and some of the bands, so it was understandable that if you wanted to promote a new counterculture in a way that helped spread the joy and the goodness of it that maybe sometimes you do have to charge admission.

CD: It’s interesting because we came across the Love-In in Penarth from newspaper clippings and people saying the police were there because everyone was worried, and the more I’ve discovered about it, the more I see it was a dance and they called it a Love-In. What’s really interesting about it is the town’s reaction to a Love-In, because they had heard about the Love-Ins in San Francisco, they were appalled that this was going to happen. It turned out to be a very straightforward, no messing, 16 year olds turning up and having a dance, some poetry. There was nothing to be worried about, essentially. But it’s interesting that just the thought of it scared people in a very conservative town.

SB: That’s the problem with the word “love”. It’s been used in history for so long in so many good, bad and otherwise ways — good, bad, and ugly — that people have a fear sometimes of it, or have an understanding about what it is if they’re intelligent enough to find out, or lucky enough to find out what it really means, a “Love-In”. The fact that people can gather together and enjoy each other’s company in a way that shares the love, then it’s great, it’s a good thing. It’s a really good thing. The fact that when things get tagged or used in media in a way other people don’t know about or understand, then it can be a little scary for them, especially if they’ve never had anything quite like it before, or at least called that.

CD: Do you think it’s even possible to put on a Love-In that reflected what was really going on if you haven’t been to one before?

SB: To reflect?

CD: If somebody anywhere in the world was trying to recreate what was happening in San Francisco, but they haven’t been there, how hard would that be to recreate?

SB: Yeah, that’s part of the problem because you really had to understand it from the bottom up and feel what it is, understand what it is, if you had been lucky enough to have been there where it started — and it wasn’t just here. I mean it started in the colleges in the East Coast, it started in some degree in Los Angeles, which did commercialize it somewhat and made it embarrassing for us up in Northern California of course, you know, when they had Jimi Hendrix opening up for the Monkees. It was like, “What?” [laughs]

In any case, there’s a thing of knowing it from the reality of having been there, versus other people having to understand it and interpret it not having been there. You’re right. It’s really not something that you can guarantee if you send it overseas to another part of the world that they’re gonna “get it.” And the whole point of really understanding what it all is gets down to the knowledge and the “getting it” part. And I know Linda, in her books and stuff, when I’ve talked to her in the past has always understood that, “Oh yeah, it’s about the ‘getting it'”. She got it. And it is that. If you understand it, then you go to it and you know what you’re gonna be doing, you’re gonna be enjoying your company with everybody there, you’re gonna dance the way you wanna dance, you’re gonna take whatever it takes to alter your consciousness, perhaps, and you’re gonna wear whatever — and they’re getting it. And participating. You’re sharing what it is with each other. And that’s what the beauty was of the “Summer of Love” type consciousness. It started before we called it that.

CD: What I think is interesting, I’ve looked into it, there was quite a hippie movement surge, people moving into Wales because it’s much less crowded than England, in the ’70s, which makes sense with what you’re saying because it’s not that they saw it on the news and said, “I’m going to be a hippie.” It had started to trickle down by that point, the experience started moving further out, so in the mid-’70s you were getting people who were actively going out — like communes or wanting to live by those values and live off the land and create their own food. — some of the pillar stones that came from that movement. They are probably a lot more worthy of being connected to the Summer of Love than a dance that was put on called a Love-In.

SB: Yeah, there’s an organic trickle-down nature that occurs with that whole counterculture movement, if you want to call it that, or new organic movement on how to live on Earth [laughs], and a lot of the people embraced not only just the scene, but all the things that surrounded the scene, which had to do with organic farming, which had to do with the environment. I mean a lot of the changes that happened here in California all happened right at that point in the beginning of the ’70s the whole thing of having Earth Day, for instance, every year, and celebrating the environment and taking care of the environment of organic food, of non-poisoned foods and things that are causing cancer, and cigarettes and alcoholism. With all of that kind of stuff out there, there started to be a consciousness that fed out from that whole culture that came from a time that they called the Summer of Love but in fact was all part of this new consciousness. And this new consciousness just spread all around the world pretty much.

I remember when we [Grateful Dead] played over at Alexander Palace in England, these people were showing up that had the same San Francisco kind of vibe that I was way familiar with, and I was kind of going, “Good! It’s still here!” Germany maybe not so much, maybe a little different [laughs], perhaps something in between the two. But England had it, the UK had it and I felt it. They were really nice, they were great folks to be able to hang with. This was September 1974. I’ve actually got footage of it that you’ll see in the Grateful Dead movie, “Long Strange Trip”.

CD: So maybe it just took a while for it to catch on …

SB: Well, yeah, all things do in life and I’m sure there are things that will come up in any culture that take time to spread. Climate change — it took a long time for people to get into the knowledge of all that and what’s going on with that.

CD: Although apparently it doesn’t exist.

SB: No, it’s been forbidden by the president to have the government people use that word, you’re right. That’s actually a fact, what?

Anyway, the fact that there was a lot more that came out of the Summer of Love than just going somewhere and gathering together and dancing and listening to music and getting high — it spread out a lot further, and the art that came with all of that, the fashions that came with all of that, and the important part of the consciousness that came with all of that. That’s really where I think the value of what was the Summer of Love still continues on with people both old, and their children and their children’s children, that spreads down. And I’ve seen it in these gatherings where people get together and have an event and you can tell that they’re “getting it”, and it would be up to them to continue it.

CD: I should touch upon briefly that you worked with the Grateful Dead. Why did you want to work with them? Why was it that you were saying, “Oh, I’m gonna go work with them?” And also, why were they so integral to the whole feeling?

SB: That’s a good question and it’s got a lot of layers of answers [laughs]. The fact that I first saw Jerry and his wife Sarah and they were playing folk music down in Palo Alto, she’s playing banjo and he’s playing guitar, and there was a band that came out of that which was pretty much Mother McCree’s Jug Band, I saw them, and then all of a sudden they were playing rock and roll and they were called the Warlocks and I was in the record business at the time and catching them at the clubs and they’d do a whole run down in Belmont down the San Francisco peninsula here. I’d hang out with them and go back in the parking lot, smoke a doobie with them, and get an idea about what their music scene was all about. So there was kind of an affinity. We had a band, the Friendly Stranger, and so it was this thing of we’re all in this new movement of this music thing together. And there were the Acid Tests, and those became a thing where friends were getting a little higher than I was at the time, and I finally was able to partake in that.

CD: Can you explain what an Acid Test is?

SB: Well, there’d be these events, gigs, concerts that the band would play, and people were being encouraged to alter their consciousness with LSD. So there was a very interesting time had by all — some of them exceptionally good, some of the very weird! [laughs]. But in all cases an experience. And Kesey visiting up in La Honda and people gathering, and music events and taking LSD. My high school buddies were going down to Stanford to Research Institute and getting paid $75 to take LSD and be studied and tested. That’s a good way to make 75 bucks.

So the Grateful Dead thing just became part of my world, and I was really, really a fan, obviously. There was Pig Pen up there doing his R&B and blues, and Jerry playing this great guitar stuff, and still some mix of some folk stuff still, and rock and roll — it was just perfect. It was all my favorite music and I just really liked the guys, and then they changed their name to the Grateful Dead and it was like, “Oh yeah, now we’re talkin’, this is getting into something good.

HSV: Wasn’t it also partly the lyrics, the message and what they were saying?

SB: Pre Robert Hunter lyrics, yeah, stuff that I related to. A lot of it came from the folk era and the blues era and the R&B stuff that already had it in the lyrics. I mean those were good songs to begin with, so I related to it that way. And it just kept getting better when Hunter started writing lyrics.

So I was a big fan of theirs. There was a time then when I was in the record business, I had a buyer for a chain of record stores who had heard that the Grateful Dead were going to start their own record company, and I thought, well, this is maybe a good time to give them a little idea of what I could bring to that particular idea, if just nothing else, just giving them some ideas, and/or be involved with them directly. In 1972, they said, yeah, we got your proposal here, we read it and come up here and have a meeting with us up here in San Rafael. So I got to have a meeting with Ron Rakow who was the money guy who had written the “so what” papers, which were the ones that he had hallucinated on and thought it would be good to have these Good Humor trucks driving around selling Grateful Dead records instead of Warner Brothers, and be in charge of their own future, as it were. My thing was just having the experience of having been a fan and being in the record industry and radio, and having also a certain amount of new ideas of how to go about having their own company.

So it was Jerry and Rakow at the big conference table in the room and we started talking a little bit about what they were planning to do. Rakow left the room for whatever business he had to do, and then just disintegrated into me and Jerry talking about growing up in San Francisco. We had a lot of stories to commiserate back and forth with. And at the end of just having a good time talking with each other, he left the room and went over to Rakow and said, “Yeah, he’s on. Hire him.” So it was just one of those kind of things.

It turned out to be a wonderful, wonderful experience. I’ve never felt so special to be close to somebody that important in my life who I’d admired for a long time and valued as a close friendship in having somebody that really I stole a lot of personal ideas of how to think and behave and look at things, just from being around him. I appreciated having that kind of experience. And with the rest of the band, people got along really fine. I had an interesting time working with in the studios with them and understanding how, in cases of taking all the notes of what we were recording and stuff that they literally, in Jerry’s case, saw their music. So there were descriptive images that would be noted how the song, or that take, related in a visual way.

So the experience was amazing. Working on the Grateful Dead movie with them showing the film people how it was going to be laid out for them onstage, and their movement, where the interviews could go on with people in line, some of the real stars in the fandom world were and taking the film guys around to them. All of those kinds of experiences were like a dream. Like a dream come true. It was amazing and wonderful. I value that experience in my life as something very, very special. I really respect the fact that I was allowed to do that, to be with them, for those years. It was great.

2017 Tile stairs @ end of California Street

CD: I get the feeling of being in San Francisco that they’ve been so important, they’ve connected with so many people. However, internationally — I don’t know if this is because of my own upbringing — the names Hendrix, Janis Joplin, Jefferson Airplane are more well-known to me than the Grateful Dead. Do you think that’s accurate?

SB: Oh yeah — and we like it that way. [laughs] It’s our secret little world that we’d just as soon leave it here at home. Everybody understands it, feels it, and knows why it’s so special. You see Jerry up there on stage smiling. Maybe you saw that image in my editing room of Jerry smiling, there’s that moment. And people would literally come for that, literally just live for that moment because whatever that energy was that they were able to produce, there with their fans, with the people who really, really got it, loved it, those people were what the Grateful Dead’s energy was really meant to be, and for. And then beyond that, the consciousness of how it treated the business that they were in also was another part of it, too. They really weren’t just the same kind of band — initially and through the main period of their journey — as other bands. And that may be the reason people didn’t get it in other parts of the world, or other parts of the Western world, anyway. Although they did play in Egypt where Anwar Sadat was a fan, which, when you have the president of Egypt liking them, it was like oh, maybe it has spread a little way. I used to get fan mail for the Deadhead office from Saudi Arabia! It was like, “Oh my goodness!” Isis has not got there yet … good!

Anyway, yeah, they were uniquely different than a lot of the other commercial bands that were out there, and because of that probably not as well known or appreciated as they were here. The appreciation that they had here in the United States generated an incredible social phenomenon of a following that to this day continues to add new members, new fans. It’s like, wait a second, these guys have been around — now Jerry’s been gone quite a while — but still generating the same interest, the same love, the same excitement about music. I get these cover band videos that people send me that are wonderful. These are teenage girls singing “Scarlet Begonias” Whoa! This is great. These people are still keeping that same thing alive. So there’s something real about the essence of what they brought that won’t go away. The Grateful Dead for me is a phenomenon that, again, I feel very privileged to be a part of and be a fan of and to still be appreciating and be able to continue to share.

CD: We should probably wrap this up in terms of Jerry, and you’re right, I went on the Wikipedia page and list of members in the Grateful Dead is very long, because obviously in re-generations, there’s that. But tell me, what happened to Jerry?

SB: What happened to Jerry? I think the one thing he was, was to be an artist, a musician that loved to be able to play with other members and share that musical experience of producing a fun, interesting night of music. And what happened was, all of a sudden with the popularity of them, in the United States especially, was this whole crown of celebrity-dom that he had to wear. And I think the weight of that probably caused him to become a little different than he probably would wanted to have been. It made it hard for him at times to escape that. And some of the escape methods that he used were detrimental to him. He often told me that some of the best things that he’s felt were in that realm of escapism using certain things to do that with, and I thought, well, that’s not good.

It was at that point in time when I started seeing it happening that I had to excuse myself from something that was getting to be a sad scenario that I thought was not gonna have a good ending. And it didn’t.

But quite honestly, I think a lot of the time that put into doing what he did, he put a lot of years into his years! [laughs] And that just alone — where most of us just wanna live to 80, 90 — I’m going for 100 just cuz it sounds like a good round number — that he really filled it up for 53 years. Which seems so young to me now. They were full, and they were rich, and they were valuable, and they were loved by billions and billions of people, literally. Makes for a good tombstone.

HSV: They say he died with a smile on his face.

SB: Yeah, that’s what I heard. I don’t doubt it knowing him [laughs].

I don’t think that there was anybody that I ever spent that much time laughing with. How’s that for a good memory, you know, of somebody’s time. And the far-outness. He would tell me — and I’ve told Linda this story before too — we’d be backstage at the Keystone or some place playing with the Garcia Band, just noodling around on his guitar, and he’d say, “Hey Steve, go out and get me somebody weird.” It wasn’t hard to find!

I mean he was scientifically astute, he was literarily astute, he was musically astute, he was comically astute — he was just fun to be with. Downsides at times but that had to do with the pressure, I think, of being Jerry Garcia, dealing with all that. But I loved him anyway. Good guy to be spending time with in my life.

HSV: Chelsea, tell us who you are, how this happened.

CD: I am working on a radio documentary right now for BBC Radio Wales which, well, with 50 years since the Summer of Love coming around, did you know there was a Summer of Love in a tiny town in Wales called Penarth? They had their very own in August of ’67. So I had the terrible job of coming to San Franciso to find out what happened here, and then discover what happened all those 5,000 miles away in Wales. The program will be lots of stories. I’ve had a great time speaking to lots of people and finding out more here.

HSV: And you’d never been to California?

CD: Never been to California before.

HSV: What are your reactions?

CD: I’d always said there was only one place in the world that I would live apart from the United Kingdom, that was New York. But I’m very proud and I’m happy to say that San Francisco has made it to the list now. I absolutely love it here. There’s a really nice feeling and perhaps I’ve been hanging out in the Haight-Ashbury area. I’m feeling the community vibes! I’m really, really enjoying my time here.

HSV: You’re gonna go home wearing tie-dye and peace signs, eh?

CD: Deck me out, yeah! I’ll go to Love on Haight and buy some threads.

HSV: It’s spreading like a fungus now!

CD: I’m going to do another Love-In!